Forever Chemicals In Firefighting Foam Are Causing a Forever Problem

Contamination Of Drinking Water And Groundwater An "Environmental Can Of Worms"

11 May 2021 by Elaine Catton

EDINBURGH, Scotland

Authorities in the US, the EU and elsewhere are uncovering massive levels of legacy PFAS contamination of drinking water and groundwater resulting from firefighting foams – and fear this is just the start of it.

Experts point to an “environmental can of worms” as persistent “forever chemicals” from diffuse sources continue to build up at an alarming rate, while “contamination plumes” of these highly mobile chemicals are being found to spread many kilometres from the initial source. Regulatory authorities are struggling to keep up as the chemicals sector continues to produce and sell PFAS chemicals with unknown or inadequately researched long-term impacts on human health and biodiversity.

“You can very easily blame the regulators,” says Dr. Kerry Dinsmore, a scientist from UK consumer research charity Fidra, continuing: “But actually, is it them? Should they have to be doing this in the first place? Should they be having to go out and search for new emerging contaminants of harm? Or should that information be coming from the industry and from the chemical industry at the beginning so that we know things are safe first?”

In the US, the Department of Defense (DoD) has uncovered substantial and widespread PFAS contamination of drinking water and groundwater on and around its bases in the US and abroad. As well as shutting down wells and installing filtration systems, it has initiated multiple CERCLA (superfund) response, compensation and liability processes, established a PFAS task force and is testing the blood of its firefighters. And president Joe Biden has allocated $10 Billion USD towards the clean-up and mitigation of PFAS in drinking water.

Meanwhile, a report in 2020 by the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) says: “It has been demonstrated that the use of PFAS in firefighting foam is associated with a significant environmental concern that does not seem to be adequately addressed by the current measures in place”.

The EU is examining an outright ban on the use of PFAS chemicals in all firefighting foams, with a dossier submission due in October 2021.

Although discussed in industry circles for some time, concerns surrounding PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) rose up the public and political agendas in 2016 following the publication by the New York Times Magazine of its article “The man who became DuPont’s worst nightmare”. It charted the legal battle between residents of a community in West Virginia and chemicals giant DuPont surrounding massive PFAS contamination from one of its plants. The story gained even more publicity when it was dramatised in the movie Dark Waters.

Not only did the legal battle uncover significant failings on the part of DuPont, it also resulted in a weight of scientific evidence and, more worryingly, major and fundamental systemic problems with global implications.

PFAS is an enormous group of chemicals – experts place the number at anything from 5,000 to 9,000 – of which only a tiny handful are now regulated, and only in some countries. Their main feature relates to properties that make them resistant to heat, stains, water and grease. They are also known as “forever chemicals” because of their resistance to degradation, meaning they persist, and therefore accumulate, in the environment for hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

The specific chemical at the heart of the DuPont story is PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid). It was produced by 3M and used by DuPont since 1951 in the production of its Teflon non-stick product. Extensive independent testing and analysis conducted over seven years as part of the legal case identified a wide range of “probable links” between PFOA and kidney cancer, testicular cancer, thyroid disease, high cholesterol, pre-eclampsia and ulcerative colitis. Further studies since then have added to the list developmental delays in fetuses and children, decreased fertility, increased cholesterol and changes to the immune system.

In 2016, The US EPA updated its Lifetime Health Advisories (LHAs) for PFOA and a similar compound PFOS to concentrations (individually or combined) of 70 parts per trillion (ppt).

At the end of 2020, the EU introduced a limit of 0.1 µg/l for a sum of 20 individual PFAS, including PFOA and PFOS, in drinking water. This figure equates to 100 ppt.

Until 2003 PFOS was a key ingredient in firefighting foams used around the world to fight blazes involving petrochemicals, including aviation and vehicle fuels. Although the sale of PFOS ceased once the dangers became apparent, these foams still contain PFOA and its so-called precursors as well as many proprietary and unregulated variants with a wide range of names all sharing highly persistent long- and short-chain carbon-fluorine bonds.

While the persistence of these chemicals is beyond doubt, very little is known about the harms the wider group can cause to human health and biodiversity. With the negative effects of PFOS and PFOA now known, scientists and health experts are concerned that the plethora of variants and precursors that are continuing to bioaccumulate could be equally harmful, if not more so.

The fact that firefighting foams containing these chemicals are deployed in substantial amounts and under largely uncontained conditions during emergencies and, far more frequently, training exercises has sparked alarm among US authorities and resulted in a programme by the US Department of Defense to test groundwater and drinking water at military bases within the US and around the world.

The findings, published in 2018 as an official response to House Report 115-200 (p. 118) by the US Congress Committee of Armed Services are alarming. In the preamble to its findings, the DoD report notes: “EPA LHA levels are only guidance under the SDWA and are not required or enforceable drinking water standards.”

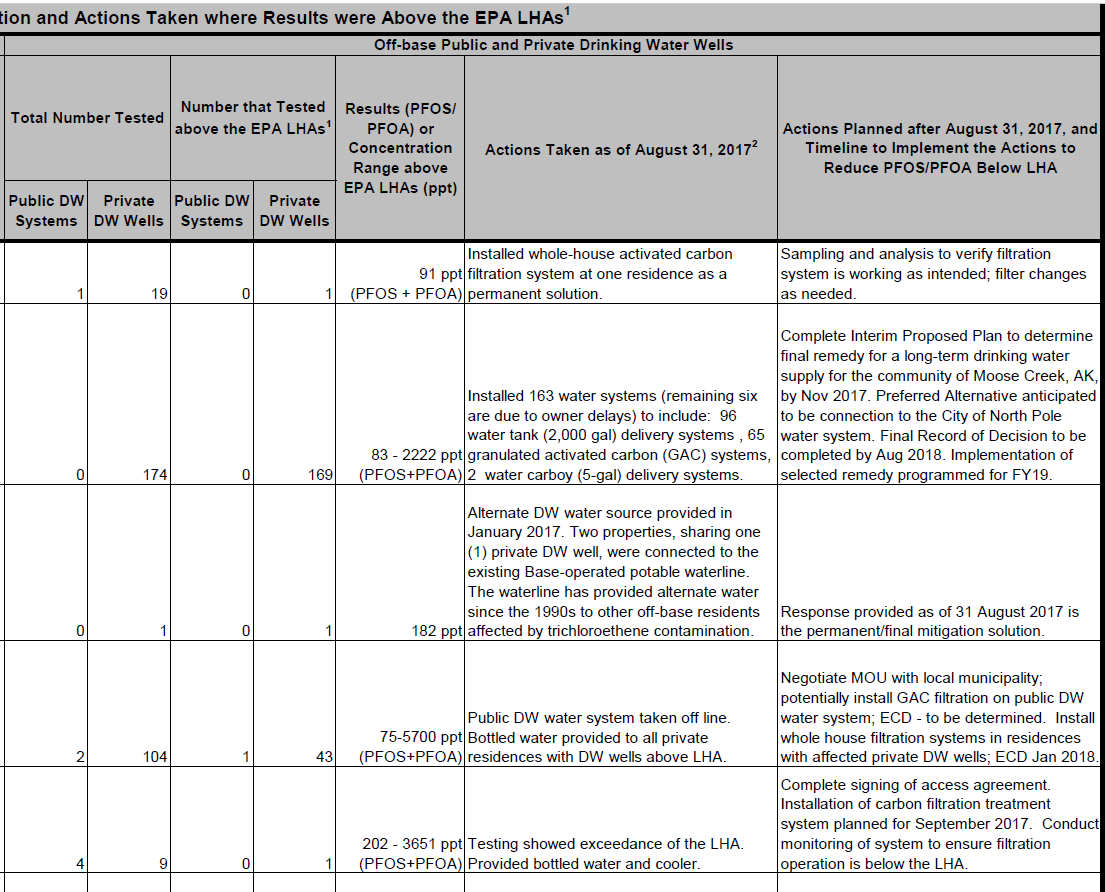

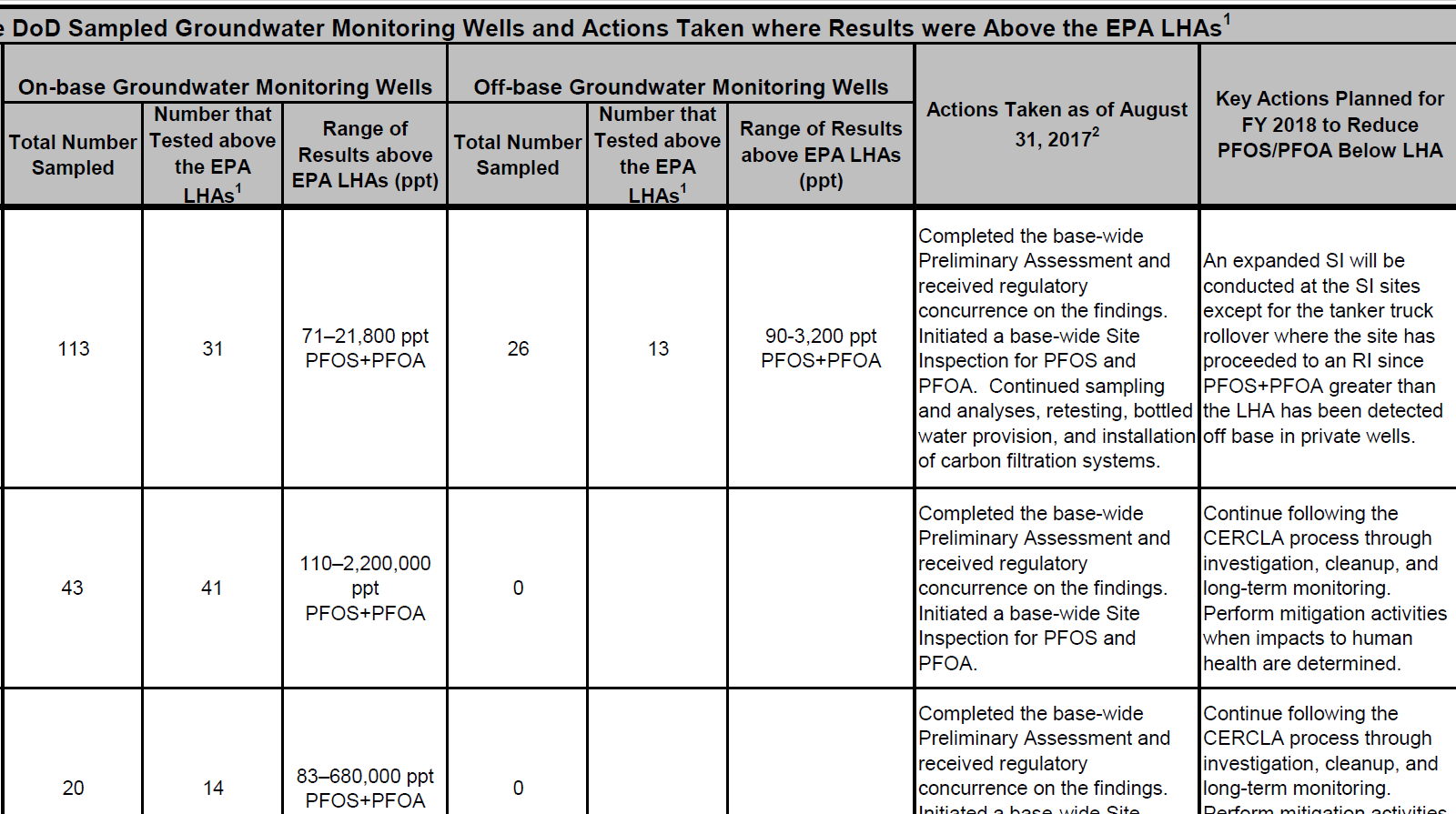

The DoD sampled a total of 5,637 drinking water systems and groundwater wells on and off military installations, and found a total of 2,221 of them contained levels of PFOA and PFOS above the EPA LHA level of 70 ppt.

A closer examination of those results shows that large numbers of them were orders of magnitude in excess of that figure. For example, in South Korea, the Stanley US Army base had up to 1,061 ppt in its drinking water, while Camp Carroll measured up to 1,066.

Meanwhile, naval bases in the states of Virginia, Pennsylvania as well as Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean had levels of between 4,900 and 8,100 ppt in their drinking water. Multiple actions were taken, ranging from the supply of bottled water to installing filtrations systems to taking entire water systems offline. The CERCLA process (Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, known also as Superfund) was initiated in at least 35 areas.

However, by far the worst contamination was found in groundwater. At military bases from New York to Wisconsin, from California to Maine, from Oklahoma to Florida, measurements were coming back in five, six or even seven figures. One well at China Lake naval base in California had a range of results from 3,800 to 8,000,000 ppt, another in Alaska had readings upwards of 10,000,000 ppt.

Foreign hosts of the US military have also been reporting major PFAS contamination suspected to have come from the use of firefighting foam at bases. In Japan’s Okinawa prefecture, the Kadena Air Base is believed to be responsible for elevated levels of PFAS in the blood of residents from three cities.

The problem was first noticed in 2016, when testing results showed a higher presence of PFAS in the drinking water that comes from a river flowing close to the air base. Subsequent blood tests showed that residents had four times more PFAS in their blood than the average Japanese. The study also noted a disproportionate number of cases of liver and cholesterol problems in the area.

In Germany, the areas surrounding the Ramstein US Airbase and Spangdahlem NATO Airbase have both had incidences of PFAS contamination, with residents advised not to eat fish from a number of rivers. A local media report from 2015 noted measurements of 82 micrograms of PFAS per kilo of fish fillet, which equates to 82,000 ppt.

A record (in German) from the state parliament of Rheinland-Pfalz from 2015 reveals that there have been concerns about PFAS contamination from the Ramstein Airbase since 2010, since when the local authorities have been carrying out testing of river water upstream and downstream of the base, as well as of ground and surface water at various points around the base.

The findings from eight tests carried out between September 2010 and December 2013 noted a sizable increase in overall PFAS concentrations from upstream to downstream and, in particular, those parts of the streams running close to rainwater reservoirs on the base. The highest of those was regularly in excess of 1 micrograms per litre (1,000 ppt) and on one occasion as much as 8.5 (8,500 ppt).

Groundwater contamination at one site close to the foam testing area was extreme, with a maximum reading in July 2013 of 163.5 micrograms per litre.

According to records released to Ooska News by Ramstein Airbase, a “major spill” of AFFF occurred 2013, when 900 litres of foam concentrate was accidentally released into an adjacent drainage ditch. The record states: “On 18.9.2013 at 11:20, the automatic fire suppression system was triggered in hangar 2512. The reason was most likely the opening of a fire hydrant nearby.”

This accidental triggering of the emergency system “caused the release of about 900 liters foam concentrate (Sthamex F-15) in 3% solution (approx. 30 cbm solution in total) into the adjacent drainage ditch and from there to the receiving creek Mohrbach”, says the log entry.

It is notable that there are no records of groundwater testing at several of the regular measurement points between July 2013 and September 2014.

The report published in June 2020 by the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) described legacy PFAS groundwater contamination attributable to firefighting foams at locations in Sweden, Jersey (the Channel Isles) and the Netherlands. Near Kallinge-Ronneby Airbase in Sweden, PFAS contamination was detected in one of two municipal waterworks supplying around 5,000 people, with levels ranging from 100-300 times over the permissible limit. “Blood samples showed significant human exposure via drinking water,” says the report.

Near Jersey Civilian Airport, groundwater in 36 properties tested positive for PFAS, with concentration remaining high in private wells for seven years (up to 98,000 ng/l).

And at Schipol airport near Amsterdam, an error in a sprinkler system at a hangar released 10,000 litres of firefighting foam, causing “substantial contamination of the soil and surface water”.

“The water resources were found to contain over 12 times the average amount of PFOS otherwise found in several reference sites in the Netherlands,” continues the report.

These are just a few examples of many point-source contamination issues and a small measure of the scale of the problem.

The US DoD is undertaking extensive testing, mitigation and remediation efforts to investigate and combat the damage done by these chemicals over the years. The use of PFOA in firefighting foams is being phased out in the US, Europe and elsewhere and being replaced by alternatives. Many fire services now use PFAS-free training foams.

However, experts are quick to point out that the problem goes way beyond drinking water, and way beyond the narrow reference point of PFOA applicable to the DuPont case and to firefighting foams in military and civilian applications. PFOA and PFOS are just two of many thousands of such chemicals that remain in use throughout the world, with very few of them subject to any form of regulation.

Fidra’s Dinsmore points to the other 5,000 or so PFAS as being potentially just as harmful but, as yet, unregulated, which is why EU scientists are pushing for a group-based approach to regulating PFAS rather than a case-by-case approach. The carbon-fluorine bond that characterises PFAS is one of the strongest bonds known in nature. “Anything that's in the PFAS group is very highly likely to be persistent,” says Dinsmore. “That's what makes them useful, but that's what makes them really environmentally damaging.”

Putting the case for the group-based approach to regulation, she argues: “There will be ones that probably are completely fine to use, but we don't know which ones they are. So, we group them all. If you find one is perfectly safe, then you can release it and you can have exemptions. But you’ve got to take this group-based approach.”

Dinsmore says that there may well chemicals for a given application that are more toxic, but that there’s very unlikely to be anything more persistent. “Whatever else you change to may have its own consequences, but they'll go away. And the thing with PFAS is that it just won't go away,” she says, adding: “I think people would have to work very hard to find a worse substance.”