Diplomacy Talks -- Trends In Food Security During Climate Change

An Assessment of Global Shifts In Agricultural Outputs

11 Feb 2022 by The Water Diplomat

EDINBURGH, United Kingdom

Diplomacy Talks and The water Diplomat Voices are a series of guest columns written by participants in different parts of the international water community.

Dr. Renee Martin-Nagle, special correspondent to The water Diplomat, highlights facts about agricultural production and how it might change given evidence of climate change.

Martin-Nagle is a globally recognized water expert and consultant focusing on surface water, groundwater, unconventional water resources, contaminants, climate change, and oceans. She currently has several affiliations: Treasurer of the International Water Resources Association; President and CEO of A Ripple Effect; Special Counsel at Eckert Seamans Cherin & Mellott LLC; Visiting Scholar at the Environmental Law Institute; Secretary and Chair of the Governance Committee of the Mount Aloysius College Board of Trustees, and Member of the Ebensburg Municipal (water) Authority. She is also an Expert Reviewer of the UN IPCC Sixth Assessment Report.

Human population is projected to grow from a current 8 billion to 10 billion by 2050, which, according to some estimates, will require a 50% increase in food supplies. Production of the main agricultural commodities – sugarcane, rice, wheat, corn, soybeans, and potatoes – has become concentrated in only a few countries, many if not most of which will experience water-related impacts from climate change such as droughts and floods.

As agricultural yields decline either acutely or chronically, the producing countries will obviously be affected, but those countries reliant on imported food will also experience consequences. Food security is critical not only for survival of individuals but also for stability of political regimes, since wide-spread famine can lead to social unrest.

To draw attention to the risks associated with the current concentration of crop production and the need to consider alternate systems in the coming decades, this article lists the countries producing, exporting and importing key commodities and then discusses water-related climate change impacts on top crop-producing areas.

Main producers and exporters of principal commodities

The agricultural commodities that are produced in greatest volume globally are sugarcane, corn, rice, wheat, potatoes, and soybeans, and each of them serves purposes in addition to providing food for humans. For example, sugarcane, the crop grown in the most volume globally, is used for fiber, fodder, biofuels and chemicals. Most corn and soybeans are slated for animal feed, with food and biofuels also being supported by the crops. On the other hand, while wheat contributes to paper, pharmaceuticals and soaps, two-thirds of the global wheat production is consumed by humans for food, and rice forms a dietary staple of more than half of the world’s population. Potatoes are the third most important food crop for humans, although like other crops they also feed animals.

Production of these crops and others, which are vital to humans and the animals eaten by humans, is highly concentrated in only a few countries. As the following chart illustrates, China is the world’s largest producer of wheat, rice and potatoes, the second largest producer of corn and the third largest producer of sugarcane. The US is the largest producer of corn and the second largest producer of soybeans. India is the second largest producer of wheat, rice and sugarcane, the fourth largest producer of soybeans, and the sixth largest producer of corn and potatoes.

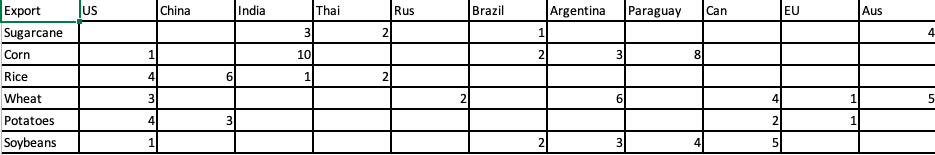

However, because many crops are utilized for a nation’s own populace, especially in China and India, the principal exporters of the key commodities are quite different from the producers.

The US is the world’s largest exporter of corn and soybeans and the third largest exporter of wheat, the EU countries together are the largest exporter of wheat and potatoes, Thailand is the largest exporter of rice, Brazil is the second largest exporter of corn and soybeans, and Russia is the second largest exporter of wheat, with Canada and Australia the fifth and sixth largest exporters of wheat.

A review of the countries importing the major crops gives a fuller picture of the global food commodity trade. China imports the most rice and soybeans, Egypt imports the most wheat, the EU countries as a whole import the most potatoes, Saudi Arabia and the US together are responsible for more than 90% of the sugarcane imports, and Japan imports the most corn, followed by Mexico. Top importers of the massive volumes of US commodities are Canada, Mexico, China, Japan, and Germany.

The impact of climate change on water supplies for agriculture

Looking at the major crop producers and exporters through the lens of climate change, the US immediately jumps out. Many of its export crops are grown in the country’s Midwest region, which has been experiencing severe and even extraordinary drought. Nonrenewable groundwater supplies much of the water for agriculture; estimates of the frequency of floods and droughts in that area during climate change vary significantly depending on the emissions scenario.

In recent years, China has experienced both floods and droughts in crop-growing areas, Brazil had its worst frost in two decades, heat and drought have affected Canadian crops, and torrential rains in Europe led to fears of fungal disease in grain crops. Australia’s wheat-growing region has had both multi-year droughts and flooding, with the excess water producing wheat with less protein.

By 2040, 32% of global cropland is projected to experience severe drought, and groundwater tables will be lower than current levels.

On a global average, 70% of freshwater withdrawals are used for agriculture, and 20% of cultivated land is irrigated as opposed to rainfed, since irrigated land is more productive.

In the future, water demand for other purposes is expected to increase, which may require a reallocation of water supplies. Indeed, as the world becomes more urbanized, water will probably be diverted to cities.

For example, due to historically low flow in the US Colorado River system, Arizona has already determined that the share of water allocated to agriculture in 2022 will be decreased in favor of cities. Sinking groundwater levels mean that tapping into aquifers cannot fill the void.

In a future where growing populations need food security, droughts impact agriculture more frequently, and groundwater tables are declining, hard decisions will have to be made about where the crops that feed the world are grown.

Related Topics

Report And Video: Experts Engage On Water Solutions For Our Changing Climate

2 Nov 2021 GLASGOW, United Kingdom

In the search for water solutions as our planet's climate changes, the International Water Resources Association (IWRA) together with the University of Strathclyde, the University ...

2 Nov 2021 WASHINGTON DC, United States

Effects of climate change will increase competition for water resources, causing food scarcity and heightening social tensions around the world within 20 to 30 years.

21 Oct 2021 GLASGOW, United Kingdom

As the Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow, Scotland, commences, Asit Biswas and Cecilia Tortajada assess the issues of water security, complexity of management of climate...