International Water Law and Transboundary Water Cooperation

24 Apr 2024

Mexico running behind on scheduled water deliveries to U.S. amid severe drought

Currently, in the fourth year of a five year cycle of water deliveries, Mexico has only delivered 30% of the water that it shares with the United States in terms of a treaty from 1...

22 Apr 2024

Albania to pilot UNECE’s scorecard for equitable access to water and sanitation

Albania has commenced a comprehensive assessment of access to water and sanitation in the country in order to generate a baseline measure of equitable access to these services. At ...

25 Apr 2024

World Fish migration foundation reports record numbers of dams removed from European Rivers

On the 15th of April a coalition of organisations operating under the name ‘Dam Removal Europe’ reported an all-time record in the removal of barriers from European rivers. In 2023...

Water in Armed Conflict and other situations of violence

3 May 2024

Research report provides interim overview of effects of war on water and health in Gaza

On the 24th of April, the Geneva Water Hub published a report on the effects of war-induced damage to water and sewage services on public health in Gaza since the 7th of October 20...

3 May 2024

Conflicts emerge over water permits and water footprint of avocado production in Mexico

During the week of the 15th of April, small scale farmers and activists from Villa Madero in Michoacan, Mexico started dismantling illegal irrigation equipment and breaching water ...

3 May 2024

International Humanitarian Conference for Sudan and its neighbours in Paris

One year after the commencement of the conflict in Sudan, France, Germany and the European Union organised an international humanitarian conference for Sudan and neighbouring count...

Knowledge Based, Data-Driven Decision Making

2 May 2024

Dakar Water Hub Keynote Address on Water Insecurity and Prosperity in West Africa

In the third week of April, Dr Boubacar Barry, scientific advisor to the Dakar Water Hub, presented a keynote address on water security as a constraint to - or enabler for – prospe...

18 Apr 2024

Global Study of PFAS concentrations in water show pervasiveness of contamination

A study published in Nature Geoscience on the 8th of April has combined data from around the world on the concentrations of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in surface an...

29 Apr 2024

Co-creation: a key but often ignored ingredient to successful water, sanitation and solid waste solutions

Stakeholders often know what solutions are needed and wanted for their contexts. Sometimes, they even have ideas on how to achieve them. External researchers and implementers worki...

Finance for water cooperation

3 May 2024

Green Climate Fund invests in increased resilience for rural communities in rural Ethiopia

The Green Climate Fund is currently entering the final phases of a project to increase the drought resilience of rural communities in Ethiopia who are facing risks in their water s...

3 May 2024

Water Resilience for Economic Resilience: Water as an Economic Connector

On the 8th of April, the Water Resilience for Economic Resilience Initiative, led by the Alliance for Global Water Adaptation, released a report on managing water for economic resi...

19 Apr 2024

Standoff in investments and potential renationalization of Thames Water

In early April, Thames Water’s parent company Kemble sent a formal notice to shareholders to announce that it had defaulted on its debt payments on a € 468 million bond. Thames Wat...

National and Local News

3 May 2024

Rehabilitating Beira: towards a more resilient coastal city

The coastal city of Beira in Mozambique – the country’s second largest city - is currently undergoing rehabilitation work to increase its resilience to the impact of cyclones which...

30 Apr 2024

A severe drought associated with El Niño is currently affecting Southern Africa, with extremely dry and warm conditions since October 2023, leading the governments of Zimbabwe, Zam...

2 May 2024

The Colombian city of Bogota is currently facing critical water shortages, with the San Rafael reservoir that supplies 70% of the water of the city having dropped to 19% of its sup...

International Water Law and Transboundary Water Cooperation

Mexico running behind on scheduled water deliveries to U.S. amid severe drought

Currently, in the fourth year of a five year cycle of water deliveries, Mexico has only delivered 30% of the water that it shares with the United States in terms of a treaty from 1944. This is the lowest amount of water delivered to the United States at this point in the cycle since 1992. Waters entering the Rio Grande below Fort Quitman are apportioned to the United States or Mexico by terms set out in the treaty. In terms of the requirements of the treaty, Mexico is required to deliver to the U.S. a minimum of 432 million m³ of water each year, on average, over a five-year cycle. As of the 13th of April, Mexico had delivered 432 million m³, as against a release of 1,295 million m³ which should be achieved on average by the end of the third year of the five-year cycle. During the previous cycle, which ended in 2020, Mexico had indeed delivered 1,295 million m³ by the end of the third year.

Farmers in Texas are worried about the impact of the water shortages, amongst others for citrus production and stock keeping. Earlier in the year, the state’s last sugar mill closed due to lack of water. Texas’ Governor Greg Abbott has renewed the drought disaster declaration for several counties in the area, and the Texas representative to the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC), Monica de la Cruz, stated that the lack of water not only impacted farmers, but also employment in the state. Manuel Morales, secretary of the Mexican section of the IBWC, stated that Mexico is working to comply with its commitments but that the water shortage is due to climate change, and he pointed out that treaty does allow more time to deliver water in the event of extraordinary drought.

The implementation of the water sharing agreement is overseen by the IWBC, which also acts to settle differences between the countries that arise as river conditions fluctuate. In the terms set out in article four of the Treaty, in the event of extraordinary drought or serious accident to hydraulic structures on the Mexican side of the border, Mexico reserves the right to make up this deficit in the course of the following five-year cycle. Already in 2020 and late 2023, Mexican farmers protested against the release of water to the U.S. during drought conditions.

The current drought is the most severe since 2011, and is currently affecting most parts of northwestern and central Mexico, with many states experiencing ‘severe’, ‘extreme’, or ‘exceptional’ drought according to the Mexico Drought Monitor .

Albania to pilot UNECE’s scorecard for equitable access to water and sanitation

Albania has commenced a comprehensive assessment of access to water and sanitation in the country in order to generate a baseline measure of equitable access to these services. At a workshop held in Albania in March this year, a data gap had been identified on vulnerable and marginalized communities, which the baseline assessment will seek to address. Already in 2022, at the 6th session of the Meeting of the Parties to the Protocol on Water and Health – a meeting convened every three years to assess access to water and sanitation across Europe - Albania had expressed interest in the self-assessment exercise.

The work will be executed under the leadership of the Water Resources Management Agency (AMBU) and the Ministry of Health and Social Protection and with the support of UNECE. The assessment makes use of an Equitable Access Score-card tool which scores responses to qualitative and quantitative questions about the management and effectiveness of water and sanitation services in the country. Using the scorecard is not an obligation for the parties to the Protocol on Water and Health, but the use of the tool is highly encouraged in UNECE countries to support the generation of a baseline measure of equity of access to water and sanitation. This enables a country to identify related priorities, to set targets to bridge the identified gaps and to evaluate progress.

Currently, some 71% of the population uses a safely managed drinking water service and 56% of the population uses a safely managed sanitation service. An EU assessment of the Albanian water sector carried out in 2016 noted some major challenges with many utilities not operational, limited sewerage networks, high levels of illegal water supply connections, intermittent water supplies and low levels of revenue recovery from the available water.

As part of the integration into the European Union, Albania will also be going through the process of aligning its water resources legislation and policies to the EU Water Framework Directive (WFD) which governs water management across the region. This includes issues such as reform of the legislative framework for water, the development of river basin management plans, capacity building of institutions to implement integrated water resources management, and the reform of the economic and budgetary framework for water management.

Legislative reform has already taken place: in 2016, the government of Albania issued water services regulations that effectively transposed the EU’s Drinking Water Directive into the national regulatory framework, laying down the requirements regarding the quality of drinking water to protecting public health from contamination risks while ensuring that drinking water is healthy and clean. The country also intends to transpose Drinking Water Directive 2020/2184 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2020 on the quality of water intended for human consumption.

In the realm of river basin management, Albania is currently preparing three river basin management plans in accordance with WFD requirements, and it has been further proposed that the equitable access scorecard should be extended to the basin level. In particular, the Ishmi River Basin is the most densely populated basin in the country and is home to the capital city Tirana and the coastal town of Durres – together accounting for 35% of the total population.

World Fish migration foundation reports record numbers of dams removed from European Rivers

On the 15th of April a coalition of organisations operating under the name ‘Dam Removal Europe’ reported an all-time record in the removal of barriers from European rivers. In 2023, across 15 European countries, at least 487 barriers were removed, compared to 325 in 2022. Just four countries accounted for a very large proportion (83%) of these removals: France accounted for the removal of 156 barriers, Spain removed 95, Sweden removed 81 and Denmark removed 72. Nevertheless, the World Fish Migration Foundation, which published the report on the dam removals, notes a recent trend in barrier removal as a tool for river restoration in Europe: the numbers have more than quadrupled since 2020.

Against the background of global losses in biodiversity, the objective of Dam Removal Europe is to restore the connectivity of thousands of kilometers of rivers across the continent, thereby enhancing freshwater biodiversity and enabling migratory fish to access their historical spawning sites. In the 2022 Living Planet Index - a measure of the state of the world's biological diversity based on population trends of vertebrate species – populations of migratory freshwater fish have been shown to have declined by 76% on average between 1970 and 2016, and by 93% in Europe specifically.

In February, there were efforts at the European Parliament to pass the Nature Restoration Law which sets a target for the EU to restore at least 20% of its land and sea areas by 2030. Over 80% of the EU’s habitats are currently found to be in poor condition, and the nature restoration law would require EU countries to restore at least 30% of the habitats covered by the law – such as forests, grasslands, wetlands, rivers and lakes – from ‘poor’ condition to ‘good’ condition by 2030. Within this, the restoration law sets a priority for the Natura 2000 areas - a network of protected areas covering Europe's most valuable and threatened species and habitats.

However, although the European Parliament adopted the Nature Restoration law in February, was adopted in February with 329 votes in favor, 275 against and 24 in abstention, it did not achieve the qualified majority of 55% of EU countries representing 65% of the EU population. Finland, Hungary, Italy, Poland, the Netherlands, and Sweden were opposed to the law and therefore it is currently in legal limbo.

Nevertheless, the EU’s Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 already commits the region to the restoration of rivers through the removal of barriers. It states that “greater efforts are needed to restore freshwater ecosystems and the natural functions of rivers in order to achieve the objectives of the Water Framework Directive. This can be done by removing or adjusting barriers that prevent the passage of migrating fish and improving the flow of water and sediments. To help make this a reality, at least 25,000 km of rivers will be restored into free-flowing rivers by 2030 through the removal of primarily obsolete barriers and the restoration of floodplains and wetlands”.

At the UN Water Conference in New York in 2023 – the first such conference in 46 years – one of the commitments announced was the Freshwater Challenge: this goal aims to restore 300,000 kilometres of degraded rivers worldwide as well as 350 million hectares of degraded wetlands. 46 countries have now become members of this challenge.

Water in Armed Conflict and other situations of violence

Research report provides interim overview of effects of war on water and health in Gaza

On the 24th of April, the Geneva Water Hub published a report on the effects of war-induced damage to water and sewage services on public health in Gaza since the 7th of October 2023. Piecing together available data on the changing status of these services and the concomitant effects on public health, the report also reviews the evidence from the point of view of international humanitarian law, which requires military decision-makers to consider the reasonably foreseeable impacts of their attacks.

These foreseeable effects include, on the one hand, the direct and visible impacts of war on water and sewage infrastructure – such as the destruction of a water tower - and on the other hand the indirect and medium-term impacts – such as the release of microbiological and inorganic contaminants into water supplies and the wider environment, which can in turn inhibit health care efforts and expose the public to environmental hazards. These impacts can ‘reverberate’, leading to detrimental impacts on public health long after the direct impact has been felt. Furthermore, although water and sewage systems may have a basic level of resilience to attacks in that the services can be repaired and restored, services that have been repeatedly subjected to damage and neglect are considerably more vulnerable. Not only does it become more difficult to restore services under these conditions, but a vicious cycle of multiple rounds of damage can also act to amplify the reverberating effects, undermining public health and individual resistance. For some people, these effects can be more dangerous than the conflict itself: UNICEF has shown that children under 5 years of age living in conflict are 20 times more likely to die from diarrhoea linked to unsafe water and sanitation conditions than to direct violence in conflict.

Foreseeing these effects is important in the context of International Humanitarian Law, which describes the rules that should guide the conduct of hostilities, including the reduction of the impact of hostilities on civilians. Article 54(2) of the 1977 Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions of 1949 explicitly states that “it is prohibited to attack, destroy, remove or render useless objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population” and includes drinking water installations and supplies and irrigation works among these objects. Beyond humanitarian law, there is a growing body of norms which serve to protect water and sanitation as part of the set of international norms designed to protect civilian infrastructure. In addition, there are diplomatic initiatives such as the recently launched initiative to spare water from armed conflicts spare water from armed conflicts .

In its second section, the report delves into the concrete effects of the war on water and health in Gaza. A total of 33,000 people have been killed in Gaza over the past seven months, and an additional 7,000 are still missing. Before the recent eruption of conflict, urban services have been damaged by several rounds of conflict in 2002, 2008, 2012, 2014 and 2021, with increasingly detrimental effects in water and sewage services. The quality of drinking water was low, and services were hampered by restrictions imposed on the development of the sector. However shortly after the eruption of the recent conflict, the emergency response plans quickly deteriorated into firefighting exercises, maintaining the functionality of priority water points, providing water to shelters, and negotiating a temporary pipeline from Egypt.

In terms of direct impact, it is estimated that 57% of water infrastructure and assets had been destroyed or damaged by the end of January 2024, including 162 wells and the headquarters of the Coastal Municipal Water Authority. 9 sewage pumping stations have been damaged along with 30 km of sewage pipelines. At the time for reporting a mere 17% of groundwater wells and one bulk water pipeline from Israel were operational. No sewage treatment plants are operational because of Israeli denial of entry of fuel. The average per capita access to water has been reduced to just one or two litres a day (as compared to the Sphere standards , which set a minimum of 15 litres per day). Hygiene is at risk, as in the shelters and camps there is less than one toilet available per 340 people, and one shower per 500 people. As a result,at least 23 children had reportedly died from malnutrition and dehydration by mid-March. Efforts to restore safe water supplies and hygiene are hampered by the limitations imposed on the transport of humanitarian aid.

In terms of the reverberating impacts, there has been a collapse of the health care system, with damages to all hospitals and the destruction of 25. 200 aid workers and 480 health workers have been killed, along with several water and sewage personnel. As a result, the World Health Organisation and many other health organisations have sounded the alarm over the spread of infectious diseases. By the end of March, more than 315,000 cases of acute watery diarrhoea had been reported, along with 81,000 cases of scabies, 46,000 cases of skin rashes and 19,000 cases of jaundice. Another 58,000 people are projected to die from injuries and disease by August 2024 if the violence continues at this level. Furthermore, 95% of the population face acute food insecurity, the highest rates ever recorded globally.

Among the longer-term impacts, there have been concerns that the flooding of tunnels with salt water would permanently pollute the main aquifer supplying water to Gaza. There are risks of increased incidences of kidney disease, dangers of the emergence of antimicrobial resistance, and the continued spread of infections.

In order to break this vicious cycle of impacts of the war on water and sewage systems, the report notes that some of the main amplifying factors that cause reverberating effects include the breakdown of the health system, the denial of electricity and fuel, poor sanitary conditions and the lack of water. severe malnutrition, and the denial of humanitarian assistance. This can all be countered through adherence to International Humanitarian Law: all those involved in military decision-making should make provisions for and facilitate the repair and restoration of the services which can prevent the transmission of disease. This means either restoring the damages directly or providing safe access and security for people who run and repair the services. The most immediately beneficial actions Israel could take are to allow the delivery of chlorine, restore the bulk water supplies, repair the water reservoirs, deliver fuel to sewage treatment plants, and provide the means necessary to operate a full-scale disease control programme.

In the report, the magnitude of the reverberating effects of war on water and health services in relation to infectious disease are judged to have foreseeable before 7 October 2023 and were foreseen publicly by several actors shortly thereafter, and future effects have now been quantified and qualified. The title of the report is therefore “Fully Foreseeable: the reverberating effects of war on water and health in Gaza”.

Conflicts emerge over water permits and water footprint of avocado production in Mexico

During the week of the 15th of April, small scale farmers and activists from Villa Madero in Michoacan, Mexico started dismantling illegal irrigation equipment and breaching water pans installed in mountain springs to supply avocado orchards. These actions were taken in protest against their perceived excessive claim on limited water supplies by the large-scale avocado farms, which has prevented water from flowing down for use by the local community. The residents do not oppose the use of water for avocado production and are offering to allow 20% of the water to flow to the farms, but wish to retain 80% of the water for use by local communities.

These events are taking place in a year in which Mexico receive less than half of its annual rainfall, and the capital Mexico City is experiencing critical shortages of water. The state of Michoacan is facing serious water shortage problems, including the reduction in the size of lakes and the reduction of river flow. Lake Cuitzeo in Michoacan, which used to support a vibrant fishing community, has faced severely declining levels since 2021, when it has only 30% of its original size. Similarly, Lake Pátzcuaro, also in Michoacan, has lost more than 50% of its volume. Both lakes are associated strongly with Mexican cultural traditions such as the ‘Día de los Muertos’ celebrations, and were popular tourism destinations, but with the current water shortages it is difficult to sustain tourism.

According to FAO, world avocado production has risen from 1.8 million tons to 8.2 million tons between 1990 and 2020. According to recent research , the production is dominated by Mexico, which accounts for 29.3% of world production. This production is highly concentrated in the Avocado Belt in the state of Michoacan, in central Mexico. Avocado production in Mexico is a lucrative industry: the annual value of avocado exports have been close to U.S. $ billion per year over the past few years, but this production is taking place in a country facing high levels of water stress, water pollution, and inequalities in access to water resources.

The production of avocados therefore comes at both an environmental and social cost, in particular through large scale deforestation and claims on local water resources by avocado farms. According to research conducted by the NGO Climate Rights International (CRI), most of the deforestation that has taken place in Michoacan and Jalisco states has violated Federal law. In addition, CRI argues that the water claims are in opposition to Mexican water law and policies.

CRI argues that under Mexican law, the decision whether to grant a water license must take into account the mean annual availability of water, calculated at least every three years, in the watershed from which the water will be drawn. Additionally, theses licenses should take account of the already existing licensing and should consider the sustainable extraction that can be achieved from an aquifer or a watershed without putting into danger the equilibrium of ecosystems.

In addition, CRI argues that the first strategic priority in the government’s current National Water Programme is to “protect the availability of water in watersheds and aquifers for the implementation of the human right to water.” However, both local protests and upholding the rule of law are challenging in this area: according to Euronews, drug cartels often make money from illegal logging and extorting money from avocado growers in Michoacan. The activists around Villa Madero have suffered threats, kidnappings and beatings in the past.

International Humanitarian Conference for Sudan and its neighbours in Paris

One year after the commencement of the conflict in Sudan, France, Germany and the European Union organised an international humanitarian conference for Sudan and neighbouring countries. This conference brought together ministers and representatives of 58 States as well as donor agencies, United Nations agencies, regional organisations and humanitarian organisations. The meeting was held both to call on the warring parties to put an end to the hostilities and to mobilise the funding required for the humanitarian response in Sudan and neighbouring countries.

Sudan has the largest number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) in the world globally: the figure currently stands at 9 million, 6.8 million of whom were displaced as a result of the ongoing conflict. Neighbouring countries have received an influx of an additional 2 million people.

Humanitarian organisations had estimated the costs of assistance to Sudan and neighbouring countries at U.S. $ 4.1 billion. During the conference, the joint pledge of donor organisations amounted to U.S. $ 2 billion. A total of 33 announcements of financial commitments were made at the conference, with a U.S. $ 511 million pledge from the World Bank, U.S. $ 354 million from the European Union and a large number of bilateral commitments from countries across Europe, the Middle East, Southeast Asia and the United States.

In November 2023, the Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) for Sudan completed a humanitarian needs and response plan which estimated that some 9 million people – including refugees in South Sudan – will experience critical needs in 2024. The HCT aims to support 6 million of these people, depending on the resources available to do so. At the time of the development of the response plan, it was estimated that U.S. $ 1.8 billion would be needed to provide this support.

The needs and response plan estimated that a total of 5.6 million people are in need of water supplies and sanitation services across the region (including refugees in neighbouring countries), of which 2.6 million were being targeted for humanitarian assistance as of November 2023. Malnutrition rates are high with more than 7 million people in need of assistance, of which 2.5 million women and children are at risk of acute malnutrition in 2024 – a situation aggravated by poor water and sanitation conditions. In South Sudan, only 35 per cent of the population have access to potable water while about 60 per cent of people practice open defecation, risking contamination of water sources.

Knowledge Based, Data-Driven Decision Making

Dakar Water Hub Keynote Address on Water Insecurity and Prosperity in West Africa

In the third week of April, Dr Boubacar Barry, scientific advisor to the Dakar Water Hub, presented a keynote address on water security as a constraint to - or enabler for – prosperity in West Africa. The keynote address was held at a seminar in Accra organized by the Water Resource Management Commission of the Economic Community of West African States and the International Water Management Institute. Dr. Barry touched on a situation analysis with regard to water resources in the region, followed by an analysis of food security challenges and responses, and ended with a review of the role of hydro diplomacy.

Firstly, in terms of the situation analysis, an important starting point is the observation that most of West Africa suffers from economic rather than physical water scarcity. Physical water scarcity is a situation in which water resources utilisation exceeds sustainable limits, and economic water scarcity is a situation in which available water resources can meet local needs, but human, institutional and financial capital is lacking to actually harness and use these resources. In West Africa furthermore, there is a water-food- energy nexus at work whereby water resources can be harnessed to delivery hydropower, which in turn enables water pumping and other forms of mechanisation for food production. Food production requires the harnessing of water resources for irrigation, and water supplies are also needed for the provision of drinking water and sanitation services.

Currently, the water-food-energy nexus is challenged through the effects of climate change. Increasingly irregular rainfalls lead to less food being produced and the need to increase food imports. In addition, higher temperatures imply higher evaporation rates, less water available in reservoirs and more power cuts. The challenge is to secure chap and regular energy to ensure more food production, more irrigated agriculture, and adequate food transport, transformation and conservation. Within this there is a need to find the right energy mix (solar, hydropower, biomass, fossil energy).

In West Africa, each element of the nexus faces challenges. Overall, a large fraction of the population struggles to get access to water, food and energy. In general terms, the urban population gets better access to these services while the rural population has barely access to clean water, a large fraction of the rural population is still food insecure, energy is provided by fuelwood that is getting scarce around villages, water is provided by irregular wells and fragile boreholes, and food is provided by rainfed crops.

The water resources of the region are governed by six River Basin Organisations, of which the Niger Basin Authority, the Volta Basin Authority, the Gambia River Development Organisation and the Senegal Basin River Development Authority are the most well-known. These organisations have developed plans for the production of energy and food, and to a lesser extent the provision of water for drinking purposes. There is a need to link power production to irrigation along the rivercourses.

Turning secondly to the issue of food security challenges in the region, a first point to note is the extreme climate variability of the area, the prevalence of both droughts and floods against the background of complex hydrology. These factors could lead to a loss in food production: in a World Bank scenario of temperature increases of 2-3°C, major changes on food production can be expected, and rain dependent farming areas could be producing only half of their current yield. These fluctuations are not unfamiliar in Africa, which has a natural legacy of extreme rainfall variability which reduced hydrological security. Africa therefore already has the experience of endemic droughts and floods, without factoring in climate change. N Evidence from Burkina Faso shows a gradual southward movement of more arid zones between 1950 and 1999.

Paradoxically, the Sahel is generally rich in groundwater resources, further underlining the difference between physical water scarcity and economic water scarcity. In addition, over time we are witnessing a steady increase in surface water flows, which - if improperly managed managed - can lead to further degradation of soils.

Taken together, a number of issues interlock to create a 'wicked problem' for the region: water scarcity, climate variability, climate change, land degradation, water quality and health issues, low agricultural productivity, poor access to infrastructure, production inputs and rural services, and the resultant drop in food security due to years of neglect of food staples and livestock sectors. This is compounded by human agency: inadequate public and private sector investments, especially in rural areas, a weak enabling environment: governance, institutions, and finally transboundary conflicts in water management. At this point, years of recurrent drought have led to food shortages and hunger.

Ongoing research in the transboundary Liptako-Gourma area in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso show an evolution in armed violence and forced displacement, in spite of a reasonably uncoordinated but well-intentioned water projects in the area. Unfortunately, the majority of investments in the water sector are focused on a single sector and do not capture the water food energy nexus. Similarly, only a small proportion of humanitarian responses in the area are multisectoral in character.

Thirdly, water can act as a vector for peace in the Sahel by working with local actors to strengthen water cooperation. High levels of undernourishment prevail in the region, and within the population groups suffering from malnutrition, smallholder farmers make up 50% of the population. Landless rural dwellers and the urban poor each make up 20%, and pastoralists, fishermen, and forest dwellers make up the remaining 10%. What is essential within this framework is the productivity of water, which is low by global standards in Africa. Investing in irrigated agriculture can make a huge difference to food production, even though the last decades have seen a decline in lending in this area. Ensuring water security requires an investment in infrastructure and institutions: water needs to be brought to the poor, and education is needed for it to be put to better use. There is considerable scope for improved agricultural production and food security through irrigation (39 million hectares) and rainfed agriculture (146 million hectares). Of the 39.4 million hectares of land that is potentially irrigable, only 7.1 million hectares, or 18% of the potential – are currently under irrigation.

Therefore, a blue green revolution is needed: Agriculture must be transformed to deliver food security, ecosystem services including clean water, flood protection and carbon sequestration. A strong agriculture sector also promotes economic growth, and resilient rural communities. This will require innovative farming methods and technologies adapted to climate change as well as translating research and knowledge into action – engaging in policy, working with practitioners, facilitating capacity building. A coherent agriculture and natural resource management programme is needed to address major issues of water scarcity and land degradation, which emphasises integration – across disciplines and scales for innovation.

The face of water management is changing: problems are becoming more complex and therefore solutions need to be more holistic, with new integrated scientific approaches, new actors, new roles, and new paradigms. The approach needs to be more demand-driven and product-oriented approach with a greater focus on developing shared goals and priority setting around high impact pathways. This will require reforms: sectoral reforms are needed to craft solutions suited to local needs and move away from a blueprint approach. There are policies which lie outside of the water sector which have a huge influence on water resources – diets, trade, agricultural subsidies, and energy, therefore harmonisation needs to be part of this reform.

Diffcult choices need to be made now rather than later: rather than sharing the pie, the pie needs to be increased, and the benefits can be shared. Investments are needed to enhance production and adapt to climate change. Water storage must be enhanced, both for agriculture – water and for the environment. Balance needs to be found between upstream and downstream, between productivity and equity, between the needs of this generation and those of the next, and therefore our current consumption patterns need review.

An integrated approach to agricultural water management requires asking the question how the water resources available in a basin can be used to its greatest advantage (e.g. how to minimize outflows of water that do not contribute desired returns). To do this we need to consider the entire spectrum of agricultural water management investment options. We need to recognize multiple uses and users of water: energy, drinking water, environment, industry, agriculture ... dealing with competition and sometimes allowing a shift of water from agriculture to other (higher value?) uses. We need therefore to understand dynamics within & across field, system and basin scales.

For such planning it is necessary to assess upstream-downstream interactions as well as the impacts of proposed interventions. It is necessary to look at increasing the economic productivity of all sources and qualities of water – surface water, groundwater, rainfall, and wastewater. For this, we need also to recognize the key role of reliable data as basis for sound management & decision-making and to dvelop and implement appropriate policy and institutional reforms when required.

Some of the best bets within this spectrum include integrated soil fertility and water management in rainfed areas, revitalizing underperforming irrigation, sustainable groundwater management, safe reuse of wastewater use, improved planning and allocation of river basin water , improved wetland management in agricultural landscapes, water and land for pastoral livestock systems, and a global soils, water and ecosystems knowledge base.

Hydrodiplomacy is a very important ingredient in this blue green revolution. Africa’s water resources are predominantly transboundary in nature, which means that any form of appropriation or control by individual States is impossible. The example of the Senegal Basin River Development Authority stands out in this regard, as it emphasises the collective right of use, enjoyment and administration of shared waters. For this reason, it has been nominated twice for the Nobel Peace Prize. Joint transboundary water management for collective progress requires political commitment at the highest level as well as a clear legal framework.

Similarly, the Gambia River Development Organisation stands out for its leadership in the region. Cutting across three river basins in four countries with three working languages, this organization looks back at 45 years of successful cooperation between states. It has resulted in sub-regional integration of infrastructure through 1677 km of electricity grid, a guarantee of mutual stability and peace, and the protection and conservation of ecosystems and measures to adapt to climate change.

Finally, the initiative of the Dakar water Hub deserves mention to support one of the world’s first transboundary agreements on subterranean water through the cooperation agreement on the Senegalo Mauritanian Aquifer.

All of this shows us the pathway for a blue green revolution in the region to enhance water and food security in the context of peaceful transboundary cooperation.

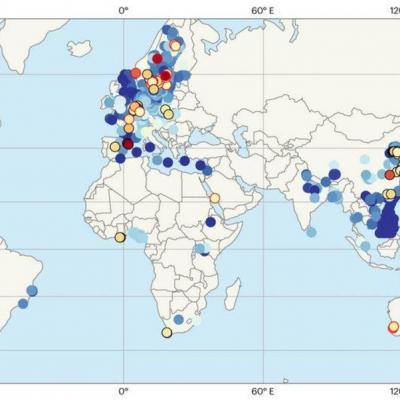

Global Study of PFAS concentrations in water show pervasiveness of contamination

A study published in Nature Geoscience on the 8th of April has combined data from around the world on the concentrations of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in surface and groundwater to help improve mitigation measures, such as providing regulatory guidance. PFAS substances are a class of more than 14,000 synthetic chemicals which have been used for more than 70 years in a broad range of industries and consumer products. Their popularity stems from the fact that they are water and oil repellent as well as being resistant to heat. Because of this, PFAS chemicals are used in the production of products such as lubricants, food packaging materials, extinguishing foam, non-stick coatings on pans, clothing, textiles and cosmetics.

However, despite their obvious utility, PFAS substances have raised concern because of their persistence in the environment (leading to them being popularly dubbed as ‘forever chemicals’). They therefore accumulate both in the environment and in the human body and, although the science of PFAS is still emerging and there are thousands of different chemical compounds to be considered, most of them are considered to be moderately to highly toxic and in humans they are currently associated with thyroid disease, increased cholesterol levels, liver damage and kidney and testicular cancer.

Regulators across the world have therefore proposed maximum concentrations of PFAS chemicals in drinking water. Interestingly, as more becomes known about PFAS substances, the European Food Safety Authority has gradually adjusted its estimates of safe levels of PFAS in the human body downward since 2008. According to the EU’s drinking water directive , the sum of the concentration of all PFAS chemicals in drinking water should not exceed 0,5 µg/litre. In the article, the researchers mention that one of the most restrictive recommendations for PFAS levels is that by Health Canada which recommends the sum of all PFAS levels to be lower than 30 nanogrammes per litre.

To generate a global overview of PFAS contamination, the researchers consulted a total of 273 environmental studies that had been conducted since 2004. Together, these studies included data for over 12,000 surface water and 33,900 groundwater samples from around the world. On the basis of the results from these samples, it was possible to assess to what extent the pollution exceeds existing regulatory norms. Of course, since the regulatory norms differ from one country to the next, the fact that PFAS levels exceed the norms has a different implication depending on the country in question.

The researchers found that PFAS are prevalent in both surface- and groundwater around the world. A map generated from the sources suggest that Australia, China, Europe and North America are hotspots for PFAS contamination, although the researchers point out that these areas are also areas where there is a high level of water sampling, so these areas may be somewhat overrepresented simply because of a relative lack of data in other areas.

Furthermore, areas which have high levels of PFAS contamination are either located close to industrial production areas and landfills, or to areas where firefighting foam (‘aqueous film forming foam, (AFFF)’ is produced or used. In areas where there were known sources of either category of PFAS, in the majority of cases the samples exceeded the regulatory norms, independently of which regulatory framework was applied. In areas where there were no known PFAS sources, there were nevertheless high incidences – in the range from 15% to 50% - of samples that exceeded the regulatory norms.

The researchers also attempted to classify and compare different kinds of PFAS substances used in 943 different consumer products. Across the wide variety of chemical substances within this class, this proved to be challenging, also because the studies on which the researchers depended did not always go into his level of detail. Nevertheless, they were able to show that two subclasses of PFAS, i.e. fluorotelomers and perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids were the most used in consumer products.

Co-creation: a key but often ignored ingredient to successful water, sanitation and solid waste solutions

Stakeholders often know what solutions are needed and wanted for their contexts. Sometimes, they even have ideas on how to achieve them. External researchers and implementers working in development projects need to understand this, and know when, how and where this is crucial. This was the overarching message that resonated in two workshops held during the Uganda Water and Environmental Week a few weeks ago in Kampala.

In one of the workshops, researchers from Makerere University and the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology (EAWAG) sought to understand which low-cost water, sanitation and/or solid waste technologies were relevant for Kakooge and Wobulenzi towns in central Uganda. This is in the context of the Water, Behavior Change and Environmental Sanitation (WABES) Integrate project funded by the Swiss Agency for Development Cooperation. They gathered stakeholders from the NGO, government, town council among others to seek their views on the technologies that have or would work for the two towns.

Surprisingly, the two hours planned for the session were almost not enough. The stakeholders suggested and discussed multiple solutions including lining pits, household water treatment, and informed about private financing st others. It was clear that they had either seen the solutions work or they were confident that they would potentially work if implemented in their context.

The second workshop by the same researchers sought to understand the capacity development needs and wishes of the stakeholders at the municipal level in the two towns. In contrast to the first one, the stakeholders did not only identify training options for their shortcomings, but also went further. They prioritized the trainings, shaped the potential courses, the time requirements, the profile of trainers, level of training, and source of funds for the trainings.

Because of the two workshops, the co-created proposed solutions reflected the stakeholders’ interests and context knowledge. It also encouraged peer learning not only among practitioners, but in addition cross learning with researchers. Studies have demonstrated the importance of such co-creation exercises in research and development programs to improve the effectiveness of outcomes and maximize their contribution to impact.

However, such engagement activities and processes are not without challenges. Identifying who and how to engage, segmenting stakeholders, power status differences and uneven information sharing can quickly alter the outcomes of the engagements. Extensive engagement further demands more time and resources, which are scarce in most project contexts. While this case involved only implementing stakeholders, engagement goes beyond and incorporates intermediaries and recipients of interventions. Therefore, such activities run the risk of appearing as reducing the efficiency of projects.

Despite the challenges, it is imperative that project/program managers, whether running research or development programs incorporate context knowledge of stakeholders closer to the challenges they target. In addition, they should involve the stakeholders in co-creating solutions that work for them. Engagement activities such as the co-creation workshops above among others are avenues for this. However, this calls for allocating resources for this during program design. Above all, the realisation that engagement is not a one-time event but a process anchored on trust and relationship building is vital in these activities.

Finance for water cooperation

Green Climate Fund invests in increased resilience for rural communities in rural Ethiopia

The Green Climate Fund is currently entering the final phases of a project to increase the drought resilience of rural communities in Ethiopia who are facing risks in their water supplies and their livelihoods. The project, which is valued at U.S. $ 50 million with a life span of five years, is intended to reach 1.3 million beneficiaries, both through improved water supply for potable water & irrigation, and management systems and by investing in the rehabilitation of degraded ecosystems in the vicinity of water sources.

Ethiopia is a country which has high levels of climate related risk: 60% of the country consists of dryland areas which are experiencing increasingly unpredictable rainfall patterns, whereas a large proportion of the rural population is dependent on rainfed agriculture. A historic drought in 2015 threatened 10% of the country’s population and since the droughts that started in 2022, humanitarian needs are 40% higher than the previous drought period.

Climate projections for the country show high levels of uncertainty, and it has been estimated that droughts alone can reduce total gross domestic product (GDP) by 1% to 4%, while the effects of environmental degradation such as soil erosion can reduce agricultural GDP by 2% to 3%. Without strong adaptation measures, climate change-induced impacts are projected to result in a loss of GDP for the country.

In response, the project has been designed in line with Ethiopia’s Nationally Determined Contribution - the country’s climate action plan to cut emissions and adapt to climate impacts. The main objective of the project is to increase the resilience of the targeted rural communities to the adverse impacts of climate change by introducing new approaches to water supply and management systems which will increase the productive capacity of the community as well as the carrying capacity of the water ecosystems. Before the project began, in the target area, only 27% of the population had access to improved water sources and 43% of the population relied on unsafe water sources. In addition, only a small minority of households practice irrigation agriculture.

In the field of water supplies, the project involves the introduction of solar powered groundwater pumps, groundwater monitoring systems, boreholes and small-scale irrigation schemes. To supplement this, in the area of catchment area conservation, upstream soil and water conservation structures and watershed protection is taking place through the construction of bunds, trenches, terraces and the planting of trees. This controls runoff water during rainfall events, reducing erosion and increasing the infiltration of water into the soil which increases the ground water balance as well as improving soil fertility. In parallel, the establishment and legalization of watershed management cooperatives is underway to ensure the sustainable management and operation of the project infrastructure as well as the restored landscapes.

The project is designed to have a direct impact on 330,000 people across 73,000 households, by providing year-round access to reliable and safe water supply. In addition, the project aims to improve food security for 990,000 people indirectly through landscape protection measures that will replant trees on 5,000 hectares of land within a broader programme to rehabilitate 7,850 hectares of degraded land. Activities are to be implemented across 22 districts (Woreda’s) which have been preselected on the basis of a national disaster risk profiling census that was implemented throughout Ethiopia. Across the districts there is a total of 66 villages (Kebeles) in which village committees are active on behalf of the project. The project will focus on women and in particular female heads of households (30% of the households in the region are female headed) to increase their resilience and unleash their untapped potential as key stakeholders and community leaders in their own right.

The project is currently in a phase whereby tangible results are being achieved, including the provision of clean potable water through deep well drilling, spring development, hand dug wells and shallow wells with solar powered pump systems for the targeted communities. Given that the project main objective is supporting resilient livelihoods in the face of the adverse impacts of climate change, these activities contribute significantly to Ethiopia’s Climate Resilient Green Economy Strategy as well as its Long Term Low Emission Development Strategy .

Mr. Mikyas Sime from Ethiopia’s Ministry of Finance stated that “The project's emphasis on women, particularly female heads of households, recognizes their untapped potential as key stakeholders and community leaders. This is crucial in building resilient and sustainable communities. Communities across Ethiopia are gaining access to reliable and safe water supply, and food security is being improved for nearly a million people. These results contribute to Ethiopia's Climate Resilient Green Economy Strategy and Long-Term Low Emission Development Strategy. The project promotes climate smart small scale irrigation approach which capable the impacts of climate change, and enhancement of production & productivity. As the agriculture sector contributes around 35% of the country’s GDP, the project is a major milestone to shift the rain fed agriculture practice to climate smart agriculture approach.”

Water Resilience for Economic Resilience: Water as an Economic Connector

On the 8th of April, the Water Resilience for Economic Resilience Initiative, led by the Alliance for Global Water Adaptation, released a report on managing water for economic resilience. The report builds on 15 case studies to draw conclusions about how action on water can enable economic resilience. The report argues that in times of climate change, water has a double role, being both a major hazard of climate change as well as a powerful way of implementing resilience within the broader economy.

On the one hand, it states, climate change is impacting the economy by changing trade relationships, stranding economic sectors and key investments, and altering the relations between different groups in society. On the other hand, there are clear gaps between our climate science, the process of economic planning, and our investment decisions. Resilience is necessary for economic planning, and water provides us with a key element to promote this resilience and steer economic development.

In its first section, the report looks at the integration – or lack of integration – of climate science into economic planning. Already in 2006, the Stern Review presented evidence on the economic costs of climate change, warning that climate change would induce economic shocks and arguing that current day investments in emissions reduction would always be less costly than the costs of adapting to the consequences of climate change. Economist Willam Nordhaus argued that that macroeconomic models do not sufficiently incorporate thinking on natural resource variability, such as for water resources. Evaluations of economic programmes and investments make use of tools such as Net Present Value (NPV), Economic Internal Rate of Return (EIRR), and cost-benefit analysis, but climate change introduces uncertainties which these tools do not incorporate. Some recent attempts have been made to factor in risks specially by tweaking investments to account for them. However, the authors argue, de-risking is not enough to capture system level changes, such as climate transformation.

Truly integrating resilience into economic thinking may imply up-front costs as planners and investors ensure that critical economic sectors can continue to operate across different climate scenario’s. However, over the medium to long term, these measures will result in increased economic efficiency as risks fall and progress is enhanced across a broad range of possible circumstances. This requires moving beyond adaptation to climate change: adaptation may ensure that sectors, projects, or assets remain prepared and responsive despite climate-related challenges. Resilience, however, is a more ambitious goal: resilience is not only the capacity to cope with a hazardous event or disturbance, but it also maintains the capacity for adaptation, learning, and transformation.

Within climate resilience, water is a central element. Water is a primary factor in 74% of natural disasters between 2001 and 2008, affecting close to 40% of the world population. Also, water is strategic because it fuses environmental, social, and economic issues: therefore, through water, we can introduce systemic and structural changes. To be effective, feasibility studies and risk analyses in the water domain must integrate both low and high climate impacts. We need system analyses to ensure confidence in the robustness of responses to a wide range of different futures. Adaptability must be incorporated into decision making, and water related impacts must be modelled and stress tested. The Water Resilience for Economic Resilience initiative is designed precisely to promote the integration of water resilience into economic thinking in the future.

In its second section, the report presents a range of case studies from across the world that demonstrate how water resilience for economic resilience is currently being planned or already being implemented. Not all 15 cases are presented here: a selection has been made from the rich overview presented.

The first case presented is Angola, which, following 27 years of war, experienced two decades of oil export-led growth. The economy has been hindered by flooding, coastal erosion and droughts which have undermined both food and water security. Economic losses in agriculture from drought are expected to increase sevenfold during this century, the productivity of fisheries is expected to decline by up to 64%, and hydropower production is expected to decline. A shift is needed from an economy driven by oil and gas towards a more diverse and sustainable economy based on natural capital, building resilience into the water resources, agriculture and fisheries, and renewable energy sectors. For this, Angola’s water resources management offices and frameworks needs to be strengthened, plans need to be developed for water storage at the basin level – including watershed storage groundwater and surface storage for climate resilience. The existing water supply infrastructure needs improved oversight and maintenance, and the existing water and sanitation utilities need to be strengthened to cope with climate change and extend service provision to peri urban areas. In rural areas, investments are needed in the expansion of water and sanitation facilities that are adapted to climate change, and municipal capacity to operate and maintain water points or support community water management efforts should be built.

The second case presented is Namibia, one of the most water scarce countries in the world and a country which is highly vulnerable to droughts. Although the country only receives 350 mm of rain per year on average, this water supports an economy with rapidly increasing water demand that revolves around mineral resources, fish exports, and tourism. Recent droughts in 2021 pushed almost a quarter of the population into food insecurity, and groundwater is becoming increasingly overexploited. Nevertheless, Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR) is an adaptation mechanism whereby heavy rain and flood events are utilized to enhance the infiltration into the ground and recharge of underground aquifers. The city of Windhoek, which faces a doubling of water demand by 2050, studied MAR as an alternative to piping water in from distant aquifers or the Okavango Delta and found that this was in fact a more cost-efficient option. Currently, surplus water not directly needed for the city is purified and injected into a local aquifer for future use. In economic terms, combining MAR with a desalinization plant yield a higher internal rate of return than when the scenario of piping water from the Okavango is included. The MAR scheme in Windhoek has therefore proven to be a reliable and cost-efficient water augmentation option to serve the rising demand and to avert the threat of water scarcity being exacerbated by droughts and climate change.

The third case presented is the Inner Niger Delta: the Upper Niger Basin and the Inner Niger Delta are an extensive interconnected wetland system extending across the Sahel and providing livelihoods for millions of people. The Niger River Basin is a huge basin, covering more two million km² across nine different countries, and it is the principal water resource for much of the Sahel region. The Inner Niger Delta expands and contracts seasonally, receiving most of its water from the upstream highlands. The Delta is a key asset both in the economy of Mali and in regional terms, supporting cereal and rice production as well as fisheries and dry season grazing. For local livelihoods, agriculture, fisheries and livestock are important sources of subsistence as well as production for the market. The Office du Niger, a parastatal agency that manages a large irrigation scheme, currently diverts water from the Niger for the irrigation of more than 100,000 hectares of land. This has made the Office du Niger known as the rice bowl of West Africa – in addition to ensuring the production of hundreds of thousands of tonnes of vegetables and other produce. In the meantime, an additional dam – the Fomi Dam – is being planned by Mali and Guinea both for hydropower purposes and to extend the scope of irrigation of the Office du Niger. However, in the light of the available water resources of the Niger River, it is questionable whether building an additional dam would indeed secure more water, especially during the dry season. This needs to be seen also against the livelihoods in the basin which have been built on the natural expansion and contraction of the river and its related wetlands: building another dam may upset the balance, disrupt livelihoods and even generate tensions and conflicts. Therefore, safeguarding and optimizing the role of the IND needs to be central in future thinking around planning and investment.

Another country facing high levels of water scarcity is Jordan. Jordan is facing significant challenges in the area of water resources, compounded by the effects of climate change which include the prevalence of droughts and changes in precipitation patterns. Jordan also ranks fifth in the world in terms of water scarcity: the available annual renewable water resources per capita is only 93m³ (well below the threshold for ‘absolute water scarcity’ which is 500m³/capita/annum). 32% of the water is surface water: amongst others the waters of the Jordan and Yarmouk Rivers, and 55% of the water is groundwater. A further 15% is added through the reuse of treated wastewater.

Among Jordan’s challenges are the growth of the population from 5 million to 11 million over the past decade, in part fueled by the influx of refugees from conflicts in neighbouring countries. Groundwater is being over-abstracted, and as a result groundwater levels are declining by an average of 5m per year. The country has experienced temperature increases of 1,5-2°C over the past two decades. Water demand is expected to increase over time, even if the existing water resources are already fully exploited. And indeed, previous planning assumed a constant increase in available water resources. However, currently the government of Jordan is working together with GIZ to develop a Third National Water Master Plan which will embrace all the critical factors that affect water utilization in Jordan, including future projections, and their impact on water supply security and overall resilience. Key focal areas for this plan are the improvement of the water resources allocation plan and alignment with investment planning, the establishment of a water resources allocation committee, a critical reexamination of water costs and pricing across different sectors, the expansion of the reuse of treated wastewater to the industrial sector, incentives for farmers to reuse treated wastewater as well as monitoring of water consumption, and the strengthening of evidence based programming through a Water Evaluation and Planning (WEAP) analysis.

Another example cited in the study is Spain, which, although not as water scarce as Jordan, faces a gradual decline in water resources and increased climate variability. The economy of southern Spain is strongly reliant on agriculture and tourism, both of which require scarce water resources. Providing water supply involves managing tensions between the needs of agrilculture, tourism, ecosystem protection, energy production and urban demand. Historically, infrastructure development has taken place to provide water services where needed. However, on the whole the infrastructure that has been developed has underperformed relative to expectations, and new prerogatives are emerging such as increasing the productivity of irrigation and balancing the need for water services with the preservation of the ecological status of water bodies. The tourism sector is important to the economy, and by combining desalination with groundwater use, the needs of this industry have been satisfied, but increasing competition over water resources is challenging further development of the sector.

In general, Spain cannot continue down the path of a growing intensity of water utilisation: it is becoming essential to ‘decouple’ economic growth from its impact on water resources. Rather than continuing to invest in bulk supplies, investments need to be focused towards taking care of the existing resources. Water infrastructure decisions need to be evaluated from an economic perspective, comparing the cost-benefit ratios of different alternatives and embracing nature based solutions. Groundwater, in particular, needs to be protected from decline in quality and overexploitation, especially as it is a strategic resource in times of drought. To enable an economic water transition, the rules for water allocation needs to be adapted to become more flexible and adapted to emerging needs while maintaining the overall aims of that transition.

Based on all the case studies covered, the publication finished with a set of seven modalities for the implementation of economic resilience through water. The first of these is introducing planning support for economic resilience across and within different sectors. Resilience needs to be defined and measured in the context of planning, recognizing the interrelationships between water and the economy. Existing economic models need to be modified to embrace the uncertainties that are associated with water, and targets for water use need to be set that recognize limitations on water utilisation and yet remain flexible to respond to changing conditions. Water scarcity and drought response programmes need to be tiered based on severity and intensity and need to respond to the needs of vulnerable groups and ecosystems.

A second modality is a procedure for risk identification and reduction: existing and future water uses in the economy need to be viewed from the perspective held against different future scenario’s. Water supply systems – including water in products and services - need to be evaluated against the background of these risks. At individual project level, climate assessments.

A third modality is ensuring that water strategies balance efficiency, diversity and resilience. Existing assumptions about the effectiveness of technical efficiency measures need to be critically revisited, the potential for the diversification of water sources needs to be investigated, and investment planning needs to be evaluated from the point of view of risk spreading, the existence of contingency plans, and the use of undeveloped spaces for flood mitigation and groundwater recharge.

The fourth modality is a review of water governance for resilience. Building resilience requires making changes to the ways in which institutions operate and how they define and implement policies, along with review of regulatory frameworks.

The fifth modality is the introduction of financial tools and incentives, within a holistic perspective that looks at water across individual projects and economic sectors. For example, the strategic use of subsidies can be considered in support of resilience. Introducing appropriate pricing for water services can be used as a means to encourage nature-based solutions. Cost-benefit analysis can consider indirect benefits and costs.

The sixth modality is tailored finance: leveraging climate finance mechanisms to pay for the additional costs of adaptation and resilience is needed, alongside a regulatory environment which makes climate-water risks visible to both investors and the public.

Finally, the seventh modality is investing in capacity building to create durable, permanent institutional changes and fuel a reorientation towards resilience. Structural reforms in water management must be complemented by dedicated efforts in capacity building and raising awareness.

Standoff in investments and potential renationalization of Thames Water

In early April, Thames Water’s parent company Kemble sent a formal notice to shareholders to announce that it had defaulted on its debt payments on a € 468 million bond. Thames Water has been experiencing financial difficulties for some time, and British regulator OFWAT has been working with the utility in recent months to develop a response to the challenges it is facing.

On the 28th of March Thames Water shareholders issued a statement indicating that a business plan had been elaborated which represented the largest ever investment programme by any UK water company, valued at over £ 18 billion (€ 21 billion) to improve customer service and adherence to environmental standards. The shareholders committed to providing an investment of 3,25 billion over and above the 500 million pledged during 2023 and pledged not to take any capital out of the business until the turnaround had been achieved.

In parallel, at the end of March, shareholders held back the investment of the 500 million pledged last year, stating that the business plan for the company was ‘uninvestable’. They argued that industry regulations, and in particular bills for customers, should be adapted. Shareholders are advocating the payment of higher water bills. Thames Water has indicated that water rates need to increase by 40% by 2030 for the company to be able to address its current debt of € 16.4 billion. Failing the securing of private investment, Thames Water would need to be renationalized.

By mid-April, without a clear solution in sight, government contingency plans for renationalization of the utility were reportedly further refined. In terms of the recent plans, the utility would be given a parastatal status – operating at arm’s length from government – as an interim measure allowing government more control over the internal reorganization prior to its reprivatization. According to the Guardian and the Financial Times , the company could be broken into two entities: one “London Water” company serving the capital and a “Thames Valley”.

In the event that a private sector solution is not found, some investors stand to lose up to 40% of their investments. This prospect has reportedly prompted a wider sell off of bonds by shareholders of other utilities in the U.K. , even though the financial position of utilities such as Southern Water and Northumbrian Water is much stronger than that of Thames Water. Similarly the bonds at Thames Water’s parent company Kemble are currently trading at a discount as a result of investor concerns surrounding the utility.

National and Local News

Rehabilitating Beira: towards a more resilient coastal city

The coastal city of Beira in Mozambique – the country’s second largest city - is currently undergoing rehabilitation work to increase its resilience to the impact of cyclones which regularly form on the Indian Ocean, and which have a major impact on infrastructure and livelihoods in Southern Africa. Following the impact of Cyclone Idai in 2019, the Municipal Council of Beira, with the support of the Netherlands government, UN-Habitat, and the Arcadis Shelter Programme, developed the Beira Municipal Recovery and Resilience Plan . This plan focuses on five priority areas of infrastructure development: coastal protection, drainage, sewage, solid waste, and roads infrastructure. Within this, the Dutch engineering organization Deltares is supporting the city of Beira to develop a response to the annual flooding of residential areas due to intense rainfall.

Beira is a rapidly growing city – the annual urban population growth rates have averaged 3% for the past four years, and therefore the city is set to double in size over the next twenty years. It is important to accommodate the new inhabitants and above all to ensure a safe living space for its residents. This is all the more so in view of the climate risks to which the city is exposed: in 2019, an intense tropical cyclone – cyclone Idai – made landfall directly at Beira, with wind speeds of 194 km/h and gusts up to 280 km/h leading to catastrophic damage to the city and the loss of 1,000 lives across Mozambique. The storm still ranks as the second deadliest on record in the Southern Hemisphere. An assessment team from the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies – the first team to arrive on site at the time - reported that 90% of the city was destroyed or damaged by the storm. The Municipal Recovery and Resilience Plan estimated that 70% of all houses had been partially (63,506) or completely (23,833) destroyed, alongside 176 municipal buildings.

The city of Beira lies on the delta of the Pungue River, and the low-lying land of the city requires strong coastal defences as well as adequate drainage. The existing dune ridge along the coast is too low to provide protection, and the existing man-made defences have been damaged and eroded by the sea. The port of Beira dominates the economy of the city and is an important port for Southern Africa. The industrial area of the port requires 2,600 hectares of land to carry out operational and logistical tasks and host business enterprises. In residential areas, the drainage channels need to be deepened and connected to a retention basin covering some 150 hectares of space to absorb water in times of high rainfall. New residential areas need to be built on higher land to avoid the recurrence of the destruction to private property that took place in the past. In order to create the coastal defences and increase the beach front of the city, sand will be dredged from the area in front of the port – which is currently restricting traffic into and from the port.

With the support of the European Union and the French development cooperation agency AFD, 19 million Euros is being invested in the rehabilitation of Beria’s sanitation system. The wastewater treatment plant, severely damaged during storm Idai, will be rehabilitated along with its wastewater collection and transport network. The operational capacities of the municipal operator – the Serviço Autónomo de Saneamento da Beira – SASB will be further built during the implementation of this project. As a result, a functional sanitation service will be provided to 100,000 inhabitants of the city of Beira.

Severe drought gripping Southern Africa

A severe drought associated with El Niño is currently affecting Southern Africa, with extremely dry and warm conditions since October 2023, leading the governments of Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Malawi to declare a state of emergency. According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), El Niño effects are hitting at a time of already significant protracted unmet needs, with some 18 million people are currently experiencing crisis levels of food insecurity. Central Mozambique, southeastern Angola and northeastern Botswana. Lesotho, eSwatini and southern Madagascar are also severely affected.

On the 29th of February, the Zambian President Hakainde Hichilema announced that the country had experienced extremely low rainfall, culminating in the worst drought that the country has experienced since the records began. In his speech to the nation, He linked the drought to climate change, stating that the effects were clearest in crop production, affecting a million hectares of agricultural land across 84 of the country’s 116 districts. Similarly, pastoralists had been negatively affected and in total 9.8 million people have been affected by the drought.

On the 23rd of March, Malawi’s President Lazarus Chakwera declared a state of disaster in 23 of the country’s 28 districts. According to Charles Kalemba from the Department of Disaster Management, the country experienced a slow onset of the rains followed by a prolonged dry spell which resulted in most of the crops wilting. The currently has low grain reserves and it is expected that some 2 million people may require humanitarian assistance if the situation persists.

On the 3rd of April, Zimbabwe’s President Emerson Mnangagwa also declared a state of emergency, stating that resources would be redirected towards supplementary grain imports. The drought is expected o impact 2,7 million people in the country.

The European Commission’s Joint Research Centre - with the support of the African Centre of Meteorological Applications for Development - has produced a report on the drought which shows that the drought began in Botswana in October 2023, and then intensified and expanded progressively to Angola, Lesotho, Madagascar, Mozambique, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. The most intense and widespread drought was experienced by the region during February and March.

Most countries experienced above average temperatures, in particular most of Namibia, Botswana, northern Zimbabwe, southern Zambia, and western Mozambique, which together experienced average temperature increases of more than 1,5°C, representing record values not measured since the 1960’s. The report notes that heatwaves exacerbated the impact of the lack of precipitation, and the average temperature is abnormally high registering record values since 1960. A particularly severe heatwave affected the whole Zambezi basin and in particular south-eastern Angola, eastern Namibia, Botswana, southern Zambia, western Zimbabwe and northern Mozambique. The Zambezi River is at its lowest discharge for the season corresponding to about 20% of the long-term average, severely affecting hydropower production.

One of the evolving responses to extreme weather events has been the emergence of the African Risk Capacity (ARC) Group , a specialized agency of the African Union established to support governments in their responses to extreme weather events and natural disasters. Before the start of the 2023/24 agricultural season, Malawi, Mozambique, Zambia and Zimbabwe all made the decision to participate in ARC risk pools. This system enables humanitarian actors to take out insurance on behalf of the country in question. For example, in 2022 ARC made a U.S. $ 4.2 million payout to the World Food Programme in Malawi’s as well as U.S. $5.3 million for Zambia and $1,4 million for Zimbabwe.

Water shortages in Bogota prompt rationing