International Water Law and Transboundary Water Cooperation

14 Nov 2023

On the 1st of November, the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE)’s Expert Group on Resource Management announced a call for public comment on a draft document aime...

3 Dec 2023

Landmark High Court Ruling on UK’s duties to restore and protect waterways

In a judgement believed to be the most significant UK Court ruling on the Water Framework Directive of the last two decades, on the 20th of November, the High Court of Justice in E...

12 Dec 2023

Water is life. Unfortunately, in the “era of global boiling”, water is also one of the hardest hit natural resources of a changing climate, exacerbated by drainage, diversion or po...

15 Nov 2023

UNICEF’s 2023 Children’s Climate Risk Supplement released ahead of COP 28

UNICEF has released a 2023 supplement to its 2021 Children’s Climate Risk Index (CCRI) report ahead of COP 28 – the United Nations Climate Change Conference of Parties, which will ...

Water in Armed Conflict and other situations of violence

7 Dec 2023

On the 22nd and 23rd of November a workshop was held in Geneva to discuss the call for a global alliance to spare water from armed conflicts. The overarching objective of the envis...

11 Dec 2023

The three forms of weaponisation of water In Gaza

A series of events over the past months show the systematic weaponization of water in Gaza by Israeli forces on all three fronts, i.e. the use of water to gain leverage through flo...

Knowledge Based, Data-Driven Decision Making

3 Dec 2023

Providing basic access to water within the planetary limits for surface water

In an article in Nature Sustainability published on the 16th of November, a team of researchers has assessed whether minimum human needs for water could be met around the world by ...

3 Dec 2023

Integrating Transboundary Climate Risks into the Global Goal on Adaptation

In a discussion brief produced by Adaptation Without Borders ahead of COP 28, the authors argue that transboundary climate risks need to be incorporated into the global goal on ada...

3 Dec 2023

Second Global Water Policy Report: Listening to National Water Leaders Published

The Water Policy Group has collaborated with the national water leaders of 92 countries across the world to generate insights into some of the key issues faced by decision makers i...

30 Nov 2023

Micro Irrigation in Niger:

In a publication in World Water Policy, researchers Issaka Osman and Gaoh Aboubacar evaluate the current state of development of micro irrigation, an important technology for food ...

Finance for water cooperation

3 Dec 2023

International trade rerouted as Panama Canal cuts traffic due to drought

On the 27th of November the Panama Canal Authority (PCA) launched a programme to auction transits through the canal. The new system will auction the transit three days prior to the...

12 Dec 2023

Investment Action Plan Closing the gap on investment in SDG 6 in Africa

The African Union and the High-Level Panel on Water Investments launched the Water Investment Action Plan at COP28. The Water Investment Action Plan has identified 53 national proj...

National and Local News

12 Dec 2023

Spain battles critical drought amid political division and complex water challenges

The drought situation in Spain remains severe, especially affecting the mid-southern and eastern regions. Approximately 10 million people, roughly a quarter of the country's popula...

22 Nov 2023

The city of Harare, the capital of Zimbabwe, declared a state of emergency on the 17th of November following an outbreak of cholera in the city in which 123 cases and 12 fatalities...

23 Nov 2023

Somali Disaster Management Agency director Mohamud Moalim Abdullahi announced on the 20th of November that 50 people have been killed and 687,235 people have been internally displa...

International Water Law and Transboundary Water Cooperation

UNECE opens call for input on specifications for Groundwater Resources

On the 1st of November, the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE)’s Expert Group on Resource Management announced a call for public comment on a draft document aimed at supporting decision making and reporting on groundwater projects. According to UNECE, effective reporting of groundwater resources is crucial for policy formulation, resource management, and decision-making that aligns with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

According to Peter van der Keur, one of the senior scientists initiating the draft document, the original impetus for developing the supplemental specifications for groundwater resources is to apply the UN Framework Classification for Resources (UNFC) to groundwater resources. This would extent the area of application of a framework which has until now been used for areas such as renewable energy, nuclear energy, 'anthropogenic resources', and injection for geological storage of CO2. The Water Diplomat has become aware of concerns from other stakehiolders that this framework is essentially one that is dedicated to extractive industries, which would not be appropriate for application in the realm of groundwater.

Nevertheless, the developers of the draft are more confident that this framework is needed. Indeed, it is argued that the tool addresses the environmental and socio-economic aspects of groundwater abstraction projects, including aspects on competing multiple uses of subsurface resources. In this way, it is argued, the NFC tool and in this way contributes to informed policy making on sustainable resource management, aligned with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and considering effects of climate and land-use change. The anticipated target users for the supplemental specifications are professional groundwater resource managers in field of managing groundwater quantity and quality.

At the same time, the UNECE draft document states, groundwater is ‘inadequately referenced’ in the SDG framework: it is not specifically mentioned within Sustainable Development Goal 6 on water and sanitation, with the exception of SDG target 6.6. “By 2020, protect and restore water-related ecosystems, including mountains, forests, wetlands, rivers, aquifers and lakes”, where it is mentioned only in passing. This stands in contrast to the fact that there are 53 of the 169 indicators in the SDG framework which have a relationship with groundwater. Therefore, it is suggested, in project decision making, careful consideration must be given to possible Impacts on groundwater from different perspectives to avoid unintended, adverse outcomes when the target activities are planned.

These perspectives are organized into different project evaluation categories which help to classify a project according to its anticipated score on these categories. The first such category is the environmental, social and economic viability of a project: this category attempts to classify a project according to whether the development and operation of the project can reasonably be expected to deliver positive environmental, social and economic results. It assesses whether all necessary conditions have been or will be met (including relevant permitting and contracts) within a reasonable timeframe, and there are no obstacles to the delivery of the project based on current projections.

The next category is the technical feasibility of the project: the framework helps to assess whether the project is already underway, whether sufficiently detailed studies have been completed to demonstrate the technical feasibility of its operation, and whether a commitment towards the development of groundwater has been agreed with stakeholders, including governments.

Finally, the framework explores the degree of confidence in the quantities of groundwater anticipated by the project. There are uncertainties associated with groundwater assessments, and this framework element seeks to help make a realistic assessment of the probability that the project will , or will not, deliver the groundwater supply that is being sought.

The public comment period for the document opened on the 1st of November 2023 and will close on the 31st of December 2023.

Landmark High Court Ruling on UK’s duties to restore and protect waterways

In a judgement believed to be the most significant UK Court ruling on the Water Framework Directive of the last two decades, on the 20th of November, the High Court of Justice in England ruled that the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) had failed in its duties to review, update and implement measures to restore rivers and other water bodies. The case was brought by the Pickering Fishery Association, an angling club in Pickering, Yorkshire, working together with an environmental organization, Fish Legal.

The Pickering Fishery Association argued that a prime fishing area on the upper Costa Beck had become degraded by pollution because the Environmental Agency had failed to review, update and put in place measures to restore rivers and other water bodies as intended under the Water Framework Directive. In terms of the Water Framework Directive (WFD), EU member states need to implement the necessary measures to prevent deterioration of the status of all bodies of surface water and protect water bodies so as to achieve good ‘ecological potential’ and good ‘surface water chemical status’ by December 2027.

Concerns have been raised about the adherence of the U.K. to European water quality standards, as, although the WFD was transposed into British law in 2016, there have been incidences of divergence from EU rules. For instance, the quality of the U.K.’s rivers is currently tested only once in three years, as opposed to once a year in the EU.

In 2021, the Environment Agency had issued summary programmes of measures intended to restore all waterbodies in each of the 10 river basin management districts in England before the legally binding final target date for the achievement of the Water Framework Directive’s water quality status of December 2027. The court found that the relevant river basin management programme for the area produced by the Environment Agency had not been reviewed and updated in relation to the environmental objectives set for the upper Costa Beck. In addition, it lacked the legally required measures necessary to achieve the obligatory targets for each waterbody - such as tightened environmental permits for controlling sewage pollution.

Why we need The Freshwater Challenge at COP28

Water is life. Unfortunately, in the “era of global boiling”, water is also one of the hardest hit natural resources of a changing climate, exacerbated by drainage, diversion or pollution of water bodies as byproducts of development.

Rivers, lakes, and wetlands including peatlands are on the frontlines of the climate crisis. They are essential parts of earth’s natural carbon cycle and crucial to helping us adapt but also to mitigating climate change. Peatlands, for example, though only covering about 3% of our planet’s land, store approximately twice the amount of carbon of all the world’s forests combined. Along shallow coastal waters, unassuming seagrass meadows are estimated to be up to 40 times more efficient at capturing organic carbon than land forests. Conversely, the loss and degradation of wetlands releases stored soil carbon. Around 4% of anthropogenic emissions currently come from degraded peatlands alone, equal to the emissions of the aerospace and shipping industries combined.

These freshwater ecosystems also supply nearly all of the world’s fresh water and play a crucial role in water purification, water storage, flood control, and groundwater recharge. Physical, biological, and chemical processes (through sedimentation, microorganisms, and sunlight) in rivers help filter pollutants from water. Lakes act as natural reservoirs, storing water from various sources such as rivers, streams, precipitation. Peatlands and other wetlands, on the other hand, act like buffers – absorbing excess water during floods, and releasing it slowly during droughts.

In fact, wetlands are so central to the water cycle on earth that a world without wetlands would be a world without fresh water.

Their crucial role for climate adaptation and mitigation has been recognized across international frameworks and conventions.

But current approaches to water are not helping countries achieve their targets on climate, nature, or sustainable development. The protection and restoration of wetland ecosystems are not adequately integrated into national policy and legislation across sectors. As a result, rivers, lakes, and other wetlands are still undervalued and overlooked, and their rapid loss (faster than other ecosystems, along with their huge biodiversity, is exacerbating the at times, catastrophic impacts of climate change.

World leaders gather this week at UNFCCC COP28 in Dubai, where, earlier this year, the Presidency announced its intention to prioritise water in the climate agenda.

The Freshwater Challenge - to which Wetlands International is a Core Partner along with WWF, IUCN, TNC, UNEP, Ramsar Convention and others - is the largest river and wetland restoration initiative in history. Launched by Colombia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ecuador, Gabon, Mexico, and Zambia at the UN 2023 Water Conference as part of the Water Action Agenda, it aims to restore 300,000 km of degraded rivers and 350 million hectares of degraded wetlands by 2030 (about 30 percent of degraded wetlands), as well as conserve intact freshwater ecosystems.

To this end the Freshwater Challenge has been chosen as one of the official Water Outcomes of COP28. [Link to FWC video]

The Freshwater Challenge builds upon existing water-related initiatives and is a way to accelerate and align action to deliver commitments on climate, biodiversity, water, and sustainable development already made. Governments form the membership, and all UN countries are encouraged to join the Freshwater Challenge.

Wetlands International is proud to support a Ministerial Roundtable on the protection and restoration of freshwater ecosystems at COP28.

Research has shown that nature-based solutions can provide over one-third of the cost-effective climate mitigation needed to stabilize warming to below 2 °C by 2030 and there is a growing inclusion of coastal and marine ecosystems in climate strategies. What we need now is an equal focus on freshwater ecosystems – rivers, lakes, peatlands, and other wetlands – and rapid scaling up of these actions with the active support of all actors involved in water-related activities across sectors – from agriculture and infrastructure to finance and energy, from high-level policy reforms to local grassroots projects.

After the conclusion of the first Global Stocktake, countries should prioritise the inclusion of ambitious wetland actions in their Nationally Determined Contributions and National Action Plans for the years to come. Only through collective national leadership and political momentum will we be able to ensure a water-resilient future. We simply cannot afford inaction.

UNICEF’s 2023 Children’s Climate Risk Supplement released ahead of COP 28

UNICEF has released a 2023 supplement to its 2021 Children’s Climate Risk Index (CCRI) report ahead of COP 28 – the United Nations Climate Change Conference of Parties, which will take place in the United Arab Emirates from 30 November until 12 December 2023.

The supplement reveals an estimate that 1 in 3 children – 739 million children worldwide – are currently living in areas which are living in areas exposed to high or very high water scarcity, a situation which is likely to be compounded by the effects of climate change. Over the next three decades, a projected 4.2 billion children will be born, and they fall within the populations of concern who are vulnerable to the stressors associated with climate change. Examples of this vulnerability include the increased spread of diseases, the vulnerability to air pollution, the relatively low ability to regulate body temperature and the risk of dehydration.

This vulnerability, the report states, is particularly prominent in low-income countries. UNICEF notes an increase in the percentage of humanitarian appeals of the United Nations that arise from extreme weather from 36% in 2000 to 75% in 2021. And yet the climate vulnerability of children is not a topic that is prominent in the IPCC’s sixth assessment report or in projects supported through climate finance. Therefore, the report argues, children should be at the centre of the global response to climate change. “Adapting essential services, compensation for loss and damage, disaster risk reduction, early warning and increased investment in decarbonization can make the difference between life and death, a future or disaster, for the planet’s children”, the report states.

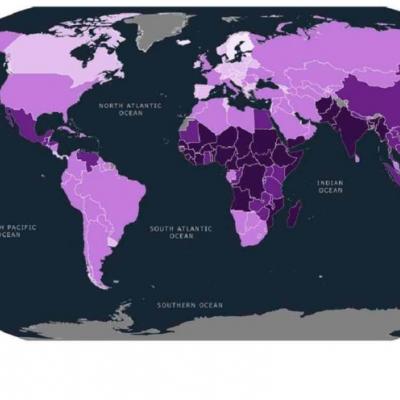

In 2021, UNICEF released a report on the Children’s Climate Risk Index which was the first comprehensive overview of children’s exposure and vulnerability to the impacts of climate change, developed to help prioritize action to support those most at risk. The report compiled geographical data which highlighted - in a series of different maps – the exposure of children to different climate related shocks such as heatwaves, water scarcity, cyclones, vector borne diseases, riverine flooding, coastal flooding, air pollution and lead pollution. By superimposing a variety of different risk indicators on a map of the world, UNICEF produced a map of the world which ranks countries on a scale from low risk to extremely high risk.

The 2021 report found that 33 countries fell into the category of ‘extremely high-risk’ and that these countries together emit less than 10 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions. Of these 33 countries, 29 are also considered fragile contexts. However, a minority of these countries have mentioned children or youth in their Nationally Determined Contributions, and they received only a small amount of global financial flows devoted to clean energy development.

Water in Armed Conflict and other situations of violence

Call for a Global Alliance to Spare Water from Armed Conflicts

On the 22nd and 23rd of November a workshop was held in Geneva to discuss the call for a global alliance to spare water from armed conflicts. The overarching objective of the envisaged alliance is to support policy level and practical actions to protect civilians during armed conflicts through the safeguarding of freshwater, water-related infrastructure, and essential services. The alliance also aims at better protecting people involved in the maintenance and repair of water services damaged or misused by parties to armed conflicts.

At a public presentation of the workshop’s findings on the 23rd of November, Professor Marc Zeitoun, Director General of the Geneva Water Hub stated that this is an important time to gather around this topic: urban warfare is becoming more common, but wars are becoming longer, sometimes decades in length in the case of permanent emergencies, and the wars are becoming more complex with overlapping layers of economic sanctions and generations of families who have adapted to a ‘biosphere of war’ in which every decision is informed by an atmosphere permeated with violence and injustice. Children, he stated, have learned to normalise the brutality and older people are denied the dignity of the rest of their lives because someone somewhere decides to keep pressing the buttons to keep launching the missiles. The impacts of damaged hospitals and schools are extreme and with our eyes wide open on the Tigray region, Yemen, Libya, Aleppo, Kharkiv and Gaza we have to concede that the impact is on water systems too. Water is not just something to fight over, it is something to use in the fight, and this has happened throughout history. In the view of Prof Zeitoun, we have reached the lowest expressions of humanity, and it is clear that the weaponisation of water is becoming more common and is keeping us in the depths of our inhumanity. Therefore, he stated, the call for the alliance was organised with a view to reduce the suffering of civilians. The weaponization of water leads to the destruction of water systems, suffering of civilians, breakdown of society, and more war. It is in this sense that the question of how we fight has become as an important a question to answer as why we fight.

There are a few things that has come to the attention of the Geneva Water Hub, which call for a coordinated response. First of all, the rules of armed conflict and the Geneva Conventions are perfectly clear on health centres and educational facilities, but they are not as clear on water and water facilities. Secondly, maybe the rules of war do not matter anymore: it is not just that there are gaps in the law, it is that they are so subjected to implementation that they may lose a lot of their value. Third, the knowledge base of the impact of destruction of water systems is growing all the time, notably in terms of reverberating effects – thanks to the research of amongst others UNICEF and the ICRC. It might be more effective if the knowledge were pooled and helped to push in one direction. Fourth, there is a growing interest in the impact of war on water systems for combatants, notably in training manuals. Furthermore, a lot of non-state actors are not in the dialogue at all and it would be good to have a safe space for them. Fifth, political will seems to be increasing around the world, suggesting that this is a good moment to push forward. The idea to have a platform where action is driven by objective information rather than by politics is a key motivation behind the alliance.

Presenting at the workshop, UNICEF’s Global WASH Cluster coordinator Monica Ramos concurred that this is a critical moment to initiative the Global Alliance to Spare Water from Armed Conflicts. The Global WASH Cluster, she explained, is a global multistakeholder platform established in 2006 with over 90 members working in over 30 humanitarian crisis contexts globally alongside up to 4,000 local and national organisations. The objective of the cluster is to strengthen system wide preparedness, enhance coordination capacity for operational response and provide clear leadership on humanitarian action. As part of its work, the Global Wash Cluster has championed the topic of attacks on water and sanitation infrastructure in armed conflicts for years and given the current state of the humanitarian crises, evidence-based policy on this topic is more crucial than ever. Amongst others the Global WASH Cluster launched the Water Under Fire Campaign in March 2019 to bring attention to areas where change is urgently needed to secure access to safe and stable water and sanitation in fragile contexts.

The misuse of water and sanitation services during armed conflicts as well as the obstruction of humanitarian access, she said, create risks that lead to public health outbreaks which gravely affect children under five, notably diarrheal diseases, which is a prominent cause of infant mortality. These impacts have been witnessed repeatedly across multiple conflicts and crisis settings over recent years in locations like Iraq, the State of Palestine, Syria, Yemen, and Ukraine. Water is used as a weapon in conflict, whether explicit or indirect. The damage inflicted takes years to address, as well as a high level of investment and to address this it is crucial that the international legal framework that safeguards water and infrastructure - including those that provide the services - are implemented and upheld. This requires compliance with international humanitarian law by parties to the conflict as well as systematic and verifiable documentation of these violations. Also, those who engage in conflict need to be made aware of the impact of military operations and understand the feasible precautions to be taken to protect water and sanitation infrastructure. Collaboration by development and peace actors is important to undertake risk analysis, complementary planning and implementation – as well as promoting the recalibration of financing systems to achieve stability and peace. There is a pivotal role to be played by a global alliance to raise awareness and provide leadership on policy and practical measures to safeguard access to water and sanitation in armed conflicts.

The three forms of weaponisation of water In Gaza

A series of events over the past months show the systematic weaponization of water in Gaza by Israeli forces on all three fronts, i.e. the use of water to gain leverage through flooding, contamination, or constriction (reducing access).

Related to the first form of weaponization, i.e. flooding, On the 4th of December the Wall Street Journal reported that Israeli forces had assembled a system of five large pumps that it could use to flood Hamas’ network of tunnels under Gaza. On the 5th of December, Israeli Defence Force chief of staff Lt. Gen. Herzi Halevi appeared to confirm that he thought that this was a good idea. In response to this plan, Prof. (Emer.) Eilon Adar of the Zuckerberg Institute for Water Research at Ben-Gurion University warned that if millions of cubic metres of seawater were to be pumped into the tunnels, this could have a long term negative effect on groundwater quality that could last for generations. Russia has warned that such a move would be considered a war crime.

Related to the second form of weaponisation, i.e. contamination, the World Health Organisation has expressed concern over the deterioration of public health in Gaza which is in part caused by limitations in access to safely managed water, the prevalence of untreated sewage, and overcrowding through the internal displacement of 1.8 million people. Before the 7th of October, 97% of the water supplies in Gaza were already unsafe to drink, with high salinity levels and contamination by e-coli. Since then, according to the WHO, the risk of bacterial infections has risen significantly due to the shutting down of the last functioning desalinization plants in mid-October. The lack of fuel has also led to the disruption of solid waste collection. The monitoring of public heath is becoming a challenge as the number of functioning hospitals has dropped from 36 to 18 within the space of one month. Despite this loss of monitoring capacity, during November, Health Policy Watch Health Policy Watch reported a massive rise in diarrhoea reported a massive rise in diarrhoea, respiratory infections and skin conditions in Gaza which was more than 16 times higher than the average.

In relation to the third form of weaponisation, i.e. constriction, the Israeli Minister of Energy, Israel Katz, made the weaponisation of electricity, water and fuel official government policy on the 12th of October, announcing that neither electricity, water nor fuel would be supplied to the Gaza strip until the hostages taken by Hamas were returned. While the average consumption of water in Gaza was 83 litres per day prior to the recent outbreak of conflict in early October, the average access to water had dropped to 3 litres per day in mid October. On the 10th of December, Israeli warplanes reportedly destroyed water supply lines in Khan Younis and Rafah, further limiting already scarce water supplies to Gaza.

Knowledge Based, Data-Driven Decision Making

Providing basic access to water within the planetary limits for surface water

In an article in Nature Sustainability published on the 16th of November, a team of researchers has assessed whether minimum human needs for water could be met around the world by using only surface water. This analysis forms part of a broader assessment of safe ‘earth system boundaries’ for freshwater. The planetary boundaries framework to which this research contributes uses earth system science and identifies nine processes that are critical for maintaining the stability of the earth’s basic environmental and life support functions. The research in this domain helps to identify whether humanity is acting sustainably for these nine key functions, one of which is freshwater.

In fact, scientists have already clarified the safe earth system boundaries for ‘blue water’, which consists of both our surface water and our groundwater. Remaining within safe planetary limits requires us to limit both the alteration of flow of surface water and the drawdown of groundwater. In rivers, flow alteration is one of the key drivers of biodiversity loss, and the rate of biodiversity loss in freshwater ecosystems is higher than any other ecosystem (83%). To meet environmental needs, we need to ensure that we alter no more than 20% of natural flows globally, leaving 80% unaltered to meet environmental needs. Currently we are operating within that limit, but 33% of the world’s land area is operating outside safe boundaries and therefore we have officially crossed the safe earth system boundary for surface water.

Groundwater, for its part, is essential to sustain plant life, supplying the root zone of plants with moisture, feeding local wetlands, and maintaining the flow of rivers. The safe operating space for groundwater is a situation in which the withdrawal of groundwater does not exceed the annual recharge rate. Across the world, 47% of basins are experiencing decline in groundwater levels, and therefore we are also operating outside the safe planetary boundaries for groundwater.

The article, however, went beyond the concept of safe planetary boundaries by examining our capacity to deliver a basic minimum quantity of water for all if we only used surface water. This is a key question for Sustainable Development Goal 6 on water and sanitation, in which the goal is to achieve universal access to safely managed water for all. Unfortunately, the researchers conclude that we are operating outside the system boundaries for minimum human needs (based, as mentioned above, exclusively on surface water).

The researchers found that 2.6 billion people live in river basins where groundwater is needed because they are already outside the safe limits of surface water diversion or have insufficient surface water to meet both the human needs and remain within safe limits. In addition, approximately 1.4 billion people live in river basins where demand management would be needed because they either already exceed the safe limits for surface water or face a decline in groundwater recharge and cannot meet minimum needs within the safe boundaries. Furthermore, 1.5 billion people live in river basins that are outside safe boundaries for surface water, with insufficient surface water to meet minimum needs, requiring changes both on the supply and on the demand side. As the researchers conclude, these results highlight the challenges and opportunities of meeting even basic human access needs to water and protecting aquatic ecosystems.

Integrating Transboundary Climate Risks into the Global Goal on Adaptation

In a discussion brief produced by Adaptation Without Borders ahead of COP 28, the authors argue that transboundary climate risks need to be incorporated into the global goal on adaptation. This is important for the first ever five-yearly UNFCCC Global Stocktake, in which countries and stakeholders will make an assessment of progress towards the achievement of the Paris Agreement on climate change. According to Adaptation Without Borders, the Global Stocktake is a nationally driven process, but this does not reflect the truly global nature of the adaptation challenge, as climate change does not respect national borders. So far, the authors argue, the Global Stocktake has a significant gap, in that it has accounted for transboundary climate risks either comprehensively, across the entire risk cascade or systematically, across sectors and regions. If this tendency continues, it will lead to an incomplete and inaccurate assessment of progress towards the goals of the Paris Agreement.

The discussion brief draws strongly on a much more detailed Global Transboundary Risk Report produced by the Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations and Adaptation Without Borders. This report is a study of different cases of transboundary climate risks which serve to illustrate the deep interconnectedness of the world’s economies, societies and ecosystems and the ways in which climate risks are transmitted over large areas. The report also shows that our adaptation response themselves can have consequences for others. It identifies ten transboundary climate risks, which include risks to terrestrial shared resources such as water and other water related risks such as agricultural commodities, oceans and coastal resources, and human health.

Cascading cross border risks exist in the water sector. For example, one country’s decision to build a dam to support their energy, water and agricultural policy objectives can jeopardize water supplies for its downstream neighbours. Similarly, the melting of glaciers generates risks by accelerating the flow of meltwater, as well as growing lakes that could burst their banks and flood communities further downstream. Also, channeling natural river courses upstream to protect or exploit water resources can increase the velocity or rivers, magnifying flood risks downstream.

It is perhaps a bit late, the discussion brief states, to fill the transboundary gap for the first Global Stocktake. However, it is important to recognize at this stage that we are missing an understanding of the transboundary and cascading nature of climate risk and therefore, we are in danger of overestimating resilience to climate change. Also, it is necessary to recognise that there are scientific barriers, as well as political and institutional barriers, to an adequate incorporation of transboundary risks into adaptation frameworks. For the next Global Stocktake therefore, amongst others, more scientific research is required that can pinpoint and quantify transboundary risks. Also, significant diplomatic barriers need to be overcome to ensure that adaptation measures are ‘just’ and do not enhance the resilience of some at the expense of others. Third, some of the more significant transboundary risks will require higher level diplomatic action, and it may be necessary to utilize other forms of international cooperation beyond national level adaptation planning to manage transboundary climate risks and coordinate between countries on joint adaptation planning.

Second Global Water Policy Report: Listening to National Water Leaders Published

The Water Policy Group has collaborated with the national water leaders of 92 countries across the world to generate insights into some of the key issues faced by decision makers in the sector. In its 2023 report, which follows on from and builds on its 2021 report, the researchers highlight the responses of water leaders to questions around current risks and challenges, how international processes can best support improved water outcomes at the national level, and issues of integration with other sectors. The report was prepared to inform global dialogue around water policy at the key water related events of 2023.

The research for the report was conducted with the support of the office of the President of the General Assembly, the African Ministerial Council on Water, the Asia Pacific Water Forum, the International Commission on Irrigation and Drainage (ICID), and the League of Arab States (LAS). The Water Policy Group worked together with the University of News South Wales’ Global Water Institute to conduct a survey – conducted among 2022 - of 92 national water leaders and explore the most influential factors affecting the achievement of good water outcomes. The concept of ‘national water leader’ as used in the survey referred to national government Ministers with a responsibility for the water portfolio, heads of national water departments or agencies, or senior officials or advisors responsible for water in a national government. The survey participants were spread across different country income classifcations, with 14 respondents from low income countries, 23 respondents from lower middle income countries, 30 from upper middle income countries, and 25 from high income countries.

From a set of ten risks and challenges, the water leaders were asked to identify the top three risks they were facing to achieve or maintain good water management. Among these, climate change dominated responses as the top challenge, followed by increasing demand for water and droughts (closely followed in fourth place by floods). Among the challenges to achieving good water management, leaders listed ‘inadequate infrastructure’ as the dominant challenge, followed by inadequate and inaccessible data and information in second place and fragmented water institutions in third place. These responses were relatively independent of the income group which countries fell into, with the exception that in high income countries, the greatest challenge is seen as ‘conflict between water user groups, including the environment’. This challenge was in fifth place for the group as a whole.

The next section of the survey was devoted to the level of helpfulness of multilateral processes in achieving ‘good water outcomes’, defined as ‘availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all’ in line with Sustainable Development Goal 6. The factor that was considered most helpful among multilateral processes was the availability of platforms that provide scientific information - including data collection and analysis – that was relevant to the country in question. The promotion of intersectoral integration of water uses - a topic widely promoted internationally – was generally placed second. The third place was jointly held by the sharing of case studies and best practices and guidance on policy and practice (perhaps by the similarity of the underlying questions – Ed.).

When asked whether the existence of a United Nations platform for countries to make public their intended future actions in relation to water would help raise the priority of water for their government, the great majority (89%) of respondents felt that this was either ‘definitely useful’ or ‘probably useful’. The main underlying reason for this was the possibility of attracting extra funding, followed by facilitating better alignment with other government priorities such as climate change, energy security and food security. When leaders were asked whether they felt that they had access to sufficient scientific services, 66% of respondents clarified that they ‘definitely’ or ‘probably’ have this access. The types of information that was considered most useful was water data and information that was applicable at the national level, followed in second place by forecasts and projections, and in third place monitoring and evaluation assessments applicable at national level.

The next topic covered by the survey was cross-sectoral integration. This section probed the importance of water to the achievement of other government objectives such as public health, food security, energy security, economic development, climate mitigation and adaptation, environment, and disaster risk reduction. In the majority of cases, water was considered to be very important - ranging from 88% agreeing it was important for energy security to 99% that it was important for climate change and environment outcomes. When water leaders were then asked whether minister from other portfolios also thought that water was important to their work, the majority felt that perceptions did not differ significantly across government departments. However, this alignment was felt to be highest for topics such as environment, climate change and disaster risk reduction, and lowest for energy security, public health, and economic development.

When probed on the question of why these differences existed, the majority felt that the importance of good water outcomes to achieving economic development was not well understood in the government. Less prominent was the view that water responsibilities are too fragmented to enable a common government view on the importance of water to economic development.

From this research, the Water Policy Group concluded that multilateral efforts on climate adaptation, disaster risk reduction, science and information, governance, as well as the commitments under the Water Action Agenda will be useful in supporting national efforts to achieve better water outcomes. They also conclude that while cross-sectoral integration may continue to be valid concern at the global level, this is of less concern at the national level. The Water Policy Group is also positive about the utility of the aggregated feedback received from water leaders to help connect global scale agendas to decision making in the water sector.

Micro Irrigation in Niger:

In a publication in World Water Policy, researchers Issaka Osman and Gaoh Aboubacar evaluate the current state of development of micro irrigation, an important technology for food security and climate resilience in the Sahelian country Niger. Irrigation is seen as the best way to increase food production and reduce the vulnerability of the country to climate change in Niger following the food crises in the country in 2005 and 2010. Small scale irrigation has developed in the country since 2010 and the production of food through irrigated agriculture with irrigated has more than doubled between 2017 and 2020. However, many challenges remain on the path to food security, and this article sheds light on the progress achieved and remaining challenges for the sector going forward.

The authors note a marked shift in Niger’s approach to irrigated agriculture over time, from large scale, state sponsored irrigation schemes in the decades after independence in 1960, to a farmer oriented approach after 2000, which, amongst others, allowed the growth of small scale irrigation.

The availability of water in Niger varies strongly from place to place: the country is semi-arid and average rainfall in the southwest is 821 mm per annum, compared with just 15.9 mm in the north east. Over the decades there has actually been an improvement in average rainfall recorded, but overall projections are uncertain and show the likelihood of both dry periods and wet periods increasing. Despite the aridity of the country, it has a fairly large irrigation potential with 270,000 hectares of land that could be irrigated. However, currently only about 30% of this potential has been realised.

From 2015, a national strategy was developed to provide harmonised and coordinated support for small scale irrigation aimed at increased and more efficient production, improved incomes, rational management of land and water resources, and coordinated access to markets. This marked a significant change in direction relative to the focus on large scale systems that had been in place previously. From 1990, though, farmer-led irrigation schemes had been supported by the World Bank, FAO and others, providing training and technical and financial support to cooperatives. The use of drip irrigation, which delivers water directly to the root zone of plants and is 90-95% water efficient, profitable and with a low environmental impact, has expanded significantly. This has been assisted by training courses in drip irrigation provided by the National Network of Chambers of Agriculture.

However, the majority of producers still use traditional techniques for irrigation, which are water inefficient. They are generally constrained financially from switching to drip irrigation, as this is generally associated with groundwater extraction which can have high associated costs. Financing and access to credit remain obstacles to expansion, although a fund for investment in food security and nutrition has been established. Given the vulnerability of agriculture in the Sahel to climate change, climate services in agriculture are also needed to help farmers select the right crop varieties, and initiatives are underway to support vulnerable sectors.

In conclusion, the authors point out that major steps have been taken in Niger to transform the irrigation sector away from the large scale state led systems and towards farmer led, small scale systems. There has been a notable expansion of micro-irrigation which can be attributed to the support provided by technical and financial partners. To improve further, changes will be needed to strengthen water resources management, strengthen farmers’ capacities, provide adequate financial support and strengthen the science-policy interface to provide effective services that can increase food security and improve the resilience of agricultural production to climate change.

Finance for water cooperation

International trade rerouted as Panama Canal cuts traffic due to drought

On the 27th of November the Panama Canal Authority (PCA) launched a programme to auction transits through the canal. The new system will auction the transit three days prior to the route becoming available, and is a response to the strongly reduced availability of water to feed the canal.

From the 3rd of November, the Panama Canal Authority (PCA) implemented additional reductions in the number of vessels travelling through the waterway in an effort to conserve water. This follows the driest October month on record, with recorded rainfall at 41% below average, which experts attribute to the El Niño climate phenomenon. Each time a ship passes through the canal, a large quantity of water is used. In response to the drought, early in the year, the maximum draft (the distance from the bottom of a ship to the water line) was reduced to 15 metres, restricting access to the canal for larger ships. Currently, the maximum draft is 13.4 metres, which is still enough to allow 70% of the ships to traverse the canal. The PCA has reduced the number of ships passing through the canal daily from 40 to 24, and this number is set to decline to 18 if the drought persists.

As a result of the reduced availability of the canal for international shipping, shipping companies are reportedly rerouting their ships through the Suez canal, the Cape of Good Hope and the straits of Magellan. On the 12th of November there were 122 ships waiting for their turn to access the canal

The Panama Canal is a key to international shipping as it enabled ships to travel between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans without having to travel around South America. 40% of all container traffic of the United States passes through the canal, and the trade through the canal is worth some 270 billion dollars a year. The canal requires large amount of freshwater to operate, which is drawn from Gatun lake, whose levels have been declining steadily since the first measurements in 1965.

Green Climate Fund's race against time for water security

In September 2023 the Green Climate Fund (GCF) published the outlines of its water sector strategy under the heading “Running dry: racing against time to secure our water future”. This follows its publication last year of the draft sectoral guide for water. Water security is central to the activities of the GCF: it has currently mobilized U.S. $ 2.8 billion to water security across 38 projects in 58 countries. In addition, some 51% of its water projects are devoted to water security. Within this 51%, 17% of projects are dedicated to agriculture and food security, 9 % to ecosystems and ecosystem services, and 7 % to early warning and early actions. The remaining 18 % are dedicated to energy, infrastructure, health, and wellbeing initiatives.

The Green Climate Fund (GCF) recognises the urgent need for a comprehensive, innovative approach to water security. It notes that collectively, we are falling short of achieving the 2030 targets related to climate, sustainable development, and disaster risk reduction, and points out that this is especially evident in water resources management, which is a top priority sector in National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) and other regional adaptation policies. Building on the outcomes of the UN 2023 water conference, the Green Climate Fund recognises the profound and complex challenges climate change poses for global water security, such as increased scarcity, flooding, contamination, infrastructure damage, ecosystem disruption, and potential transboundary conflicts. These challenges have associated risks to public utilities, corporations and financial institutions which can disrupt operations, increase costs and potentially cause major financial losses.

Overcoming these interconnected challenges, the GCF states, will take bold commitments with innovative solutions, clear and measurable targets, institutional and policy reforms, dedicated financing, and cross-border collaboration. Amongst others, addressing these risks involves investment in weather, water, ocean, and climate sciences, which have seen revolutionary advancements in recent decades. However, significant challenges remain, such as gaps in global surface data, lack of accessibility for local communities, and insufficient scientific capacity prevent their full and effective use.

Water risks in an era of climate change involve complex interactions which are interconnected and systematic. As a result, the GCF recognizes the need for a comprehensive, innovative approach to water security that embraces this complexity. For the GCF, an appropriate response to strengthen water security for climate resilience requires a flexible and needs-based approach to projects which uses a nexus and integrated approach. The GCF invests in water security through different pathways which include water conservation, efficiency, and reuse, hydrological observation, forecasting and risk, assessment, integrated water management and SDG targets, climate resilient WASH and community knowledge. Within this spectrum of activity, the GCF underlines that although most current climate finance goes to mitigation projects, the mitigation potential of water remains largely neglected (e.g., wetland restoration and conservation). Therefore, this presents an opportunity to scale up efforts and align financing flows across different categories such as biodiversity, water management, and carbon credits. Additionally, GCF promotes sustainable water management practices that conserve resources and protect ecosystems. It supports projects that enhance community adaptive capacity, particularly for those most vulnerable to climate change.

At the level of financing, it also requires an innovative approach, viewing water as an asset class. The GCF leverages public and private investments to mobilise resources for water security and blending grants with innovative financial instruments such as water bonds, ‘catastrophe bonds’ (a debt instrument designed to raise money for companies in the event of a disaster), debt for climate swaps, etc.

To accelerate the achievement of the 2030 targets related to climate, sustainable development, and disaster risk reduction, the GCF lists six sets of actions that are needed. The first of these is increased investment in weather, water, ocean, and climate sciences to address the challenges posed by climate change and risk informed early warning systems. The second is harnessing private finance and exploring non-traditional financial instruments like equity investments, insurance, debt-swap and guarantees. Thirdly, the GCF is working to align investments for water security with climate action to create new financing opportunities for private sector linking to public sector or SMEs. Fourth, is is important to recognise the potential of water as a tool for mitigating climate change and scaling up efforts accordingly. Fifth, it advocates the promotion of sustainable water management practices that conserve water resources and protect ecosystems. And lastly, the GCF works to support projects that enhance the adaptive capacity of communities most vulnerable to climate change.

In a conversation The Water Diplomat, Bapon Fakhruddin, a water and climate leader at the GCF, highlighted a recent transition in the approach of the GCF to reviewing project proposals. Whereas in the early stages, the GCF had a ‘post-box’ approach to proposals, whereby the proposal was judged on its merits and based on the initiative of the submitting government or agency, it has over time developed sufficient expertise in the water sector to engage in co-production of projects. This implies that experiences from projects around the world can be shared with submitting entities as examples of alternative options to enrich the project concept under development, and benefit from the gradual buildup of global experience in investing in water security in a holistic and integrated manner.

On the 11th of December at COP 28, together with the French Water Partnership and the Global Water Partnership, the GCF is co-curating the agenda of a day on Transformative Climate Finance at the Water Pavilion.

Investment Action Plan Closing the gap on investment in SDG 6 in Africa

The African Union and the High-Level Panel on Water Investments launched the Water Investment Action Plan at COP28. The Water Investment Action Plan has identified 53 national projects worth U.S. $ 30 billion across 19 African countries and 15 transboundary projects worth U.S. $ 9 billion, to be implemented in the remaining years until 2030. From its inception, the Continental Africa Water Investment Programme (AIP) seeks to raise U.S. $ 30 billion annually for the achievement of water related SDG targets on the continent. Announced already at the 9th World Water Forum in Dakar in March 2022, the AIP seeks to accelerate the implementation of SDG 6 and related targets by closing a funding gap that varies between U.S. 11 billion and U.S. $ 20 billion annually. Since the launch of the programme, several countries – including Zambia and Tanzania - have launched national level water investment programmes which demonstrate the commitment towards domestic resource mobilization: Tanzania announced a U.S. $ 15 billion water investment programme in June this year, and Zambia announced a U.S. 6 billion water investment programme in July 2022.

A key aspect of the AIP is the emphasis on the role of local leadership to achieve the mobilization of funds: the programme works on the assumption that a full 90% of the necessary funds can be gained through improvements in sector governance through efficiency gains and savings. This includes the reduction in operational water losses, improved billing, appropriate technology and non-revenue losses. Furthermore, the programme builds on partnerships with the private sector to reduce risks, yielding savings in water costs incurred through improved water stewardship. And finally, a large proportion of domestic resource mobilization is expected to be achieved by mobilizing institutional investors, implementing pollution and mineral extraction taxes, increasing national budgets for water, and raising funds from local banks and multilateral agencies.

In this perspective, the proportion of investments required through bilateral and multilateral assistance as well as through international climate finance remains relatively low at 10% of the total.

National and Local News

Spain battles critical drought amid political division and complex water challenges

The drought situation in Spain remains severe, especially affecting the mid-southern and eastern regions. Approximately 10 million people, roughly a quarter of the country's population, are currently subject to water restrictions due to this prolonged condition.

In Catalonia, the ongoing water crisis has persisted for 36 months, surpassing the severity of the drought recorded in 2008. During that period, the region lacked desalination plants and had to resort to importing water by ship from Marseille to fulfill the water needs of the Barcelona metropolitan area, where over 3 million people reside.

According to the Catalan Water Agency (ACA), a combination of high temperatures, scarce rainfall, and critically low reservoir levels, barely reaching 18% of their capacity, has resulted in the most severe drought in the region's history. This particular drought is notable for both its extensive coverage, affecting over 50% of Catalan territory, and its intensity, significantly impacting water supply and the local ecosystem.

In Andalusia, Spain's most populated region with 9 million inhabitants, which is currently experiencing the lowest rainfall since the 1960s, a recent agreement has been reached regarding the financing and regulation of water use for irrigation within the boundaries of the Doñana National and Natural Park. This agreement, named the Pacto de Doñana, was brokered between the new national government, a result of a progressive coalition supported by several nationalist and pro-independence parties, and the autonomous government of Andalusia, led by the right-wing conservative Partido Popular, holding an absolute majority in the regional government.

In recent months, this natural reserve has been the focal point of debate due to a controversial regional law promoted by the Partido Popular and supported by VOX, a far-right Spanish nationalist party that denies climate change and openly opposes the 2030 Agenda. This legislation aimed to expand irrigated areas around the National Park despite historically low water levels in the main marshes caused by prolonged drought and excessive aquifer exploitation.

The surroundings of the feature extensive zones of intensive farming covering approximately 11,000 hectares dedicated, predominantly to growing berries in greenhouses. . About 1,500 hectares of this production is illegal, impacting water regulation and access, especially during drought periods. The Doñana National Board established a 7,000-hectare limit on irrigation in 1991; however, since then, water extraction from the aquifer has more than tripled

In a context characterized by intense political polarisation in Spain, the Doñana Pact signifies the first significant agreement of the legislature between the nation's two main parties, the PP and the PSOE.

The pressure stemming from a segment of public opinion due to the environmental deterioration of Doñana (which is also the habitat of the Iberian lynx), the internationalization of the conflict under the auspices of the European Commission, and the political stance of the current President of Andalusia, Juanma Moreno—who represents the moderate vision of the PP and seeks to align the party closer to the center electorate—are key aspects for understanding this change in position.

This situation notably contrasts with the stance of her party counterpart, Isabel Díaz Ayuso, the President of the Community of Madrid. She recently announced legal action against the national government concerning the Tagus Hydrological Plan. Accusing Sánchez of attempting to 'deprive' Madrid of water, Díaz Ayuso employs rhetoric similar to that of Vox, particularly concerning climate change and environmental pollution. Her government argues that the decree damages Madrid's interests and has taken the lawsuit to the Supreme Court

The new Tagus Hydrological Plan (2022-2027 cycle, established under the the EU Water Framework Directive) has emerged as the focal point of water conflicts among various stakeholders, including water users, civil and ecological associations, political parties, and several autonomous communities in Spain. The implementation of ecological flows in the River Tagus, particularly as it courses through the city of Toledo (capital of Castilla-La Mancha), holds significant implications. Firstly, it determines the impact of pollution on the upstream tributaries flowing through the Community of Madrid. Secondly, it affects the potential transfer of water from the upper section of the river to the Mediterranean via the Tagus-Segura water transfer.

This hydraulic infrastructure, established at the outset of Spanish democracy in 1979 and spanning over 240 kilometers, interconnects both watersheds, facilitating irrigation across approximately 240,000 hectares of intensive fruit and vegetable farming. These products are primarily earmarked for export to European countries and are cultivated in regions like Murcia, the southern part of Valencia (Alicante), and Eastern Andalusia (Almería), which have predominantly been governed by right-wing parties for the last two decades.

According to the Central Union of Irrigators of the Tagus-Segura Aqueduct (SCRATS), a reduction of water transfers by half through the Tagus-Segura transfer would signify the loss of 22,255 direct and indirect jobs and an estimated decrease of 927 million in regional production, according to a report by economists from Murcia.

For decades, numerous environmental associations have been denouncing the alarming condition of the Tagus River's water, attributing it to poor water treatment and regular wáter transfers. One prominent figure in this advocacy is Alejandro Cano, the president of the Platform in Defence of the Tagus River and a key member of the New Water Culture Foundation. This social and professional movement emerged in the 1990s in opposition to the Ebro water transfer project and currently advocates for a paradigm shift in water management toward more equitable and sustainable models.

According to the Ministry for Ecological Transition, up to 74% of Spanish territory is at risk of desertification due to the climate crisis and the unsustainable exploitation of natural resources, particularly water. While intensive and industrialized irrigated crops represent only 20% of the cultivated area, they consume up to 80% of the total water usage in Spain. With almost 4 million hectares under irrigation, Spain stands as one of the primary water consumers in Europe.

Citizen engagement and mobilization on environmental affairs in Spain have been very modest so far. However, the political agenda has been evolving to include a growing debate on ecological issues. An illustrative example occurred last year when a popular legislative initiative, garnering more than 640,000 signatures, succeeded in granting legal recognition to the Mar Menor, located in the Region of Murcia, as the first European ecosystem with such recognition.

In general terms, right-wing parties, such as the PP and Vox, support the development of infrastructures (dams, transfers) to increase or maintain water supply, defending the productivity associated with wáter. They consider a more liberal water management framework to be the most efficient way to conserve water. Vox proposes that water and its supply be governed by market laws and private ownership to reduce waste. On the other hand, left-wing parties propose the opposite, seeking to prohibit the 'commodification' of water and promoting moderation or reduction of consumption, even at the expense of transforming economic practices, especially in agriculture and tourism. In a context scarcity, identity issues are used to mobilize voters, making it difficult to reach a consensus on shared water resource management at the national level.

Harare declares emergency amid cholera outbreak

The city of Harare, the capital of Zimbabwe, declared a state of emergency on the 17th of November following an outbreak of cholera in the city in which 123 cases and 12 fatalities were recorded. 80% of the cases in Harare were registered in the high-density suburb of Kuwadzana in the northwest of the city. However, according to the Harare city health director Dr Prosper Chonzi, almost all of the city’s suburbs had reported cholera cases. The health ministry is working in a coordinated effort with local authorities and relief and aid groups to double the supply of safe potable water in affected areas and carry out awareness campaigns. The government is advising people to avoid buying at unauthorized vendor stands, open air marketplaces, and is advising not to attend church camps.

The 2023 cholera outbreak in Zimbabwe started in February and has gradually spread to 45 out of the country’s 62 districts, with the highest incidences in Harare and in Manicaland in the east of the country. By the 7th of November, nationwide, Zimbabwe had registered 6,685 suspected cholera cases and 136 suspected cholera related deaths by the end of the first week of November. On the 17th of November the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) launched an emergency appeal for 3 million Swiss Francs to support the Zimbabwe Red Cross Society (ZRCS), as the health needs exceed available resources and immediate was required to respond adequately to the outbreak. IFRC had previously allocated CHF 464,595 from its Disaster Response Emergency Fund (DREF) to support the relief efforts.

Zimbabwe experienced its worst cholera epidemic in 2008, when more than 100,000 cases were reported and more 4,000 people lost their lives. This occurred amid a political and economic crisis in the country which undermined an effective response by health officials. In 2018, another major outbreak took place in which more than 10,000 cases were reported and 69 deaths. In this case, it was also Harare which was the most affected by the outbreak.

The municipal water system of Harare is faced by a number of interlocking challenges. The water supply system dates from the 1060’s and provides some 704 000m³/day of water to the city, which is estimated to cover less than 40% of demand. The Harare Water Department is mandated to supply water to Harare and neighbouring towns of Chitungwiza, Epworth, Ruwa and Norton Town. The infrastructure itself is outdated and poorly maintained. In combination with poor solid waste and wastewater management and low levels (43%) access to sanitation, these conditions contribute to ongoing vulnerability to cholera outbreaks. A project is underway with Vitens Evides International to improve service levels through a variety of factors including training on leadership and business planning, attracting investment, involving local communities, and reducing non-revenue water (leakages and metering and billing).

Close to 700 000 people displaced by floods in Somalia

Somali Disaster Management Agency director Mohamud Moalim Abdullahi announced on the 20th of November that 50 people have been killed and 687,235 people have been internally displaced as a result of flash floods in Somalia. The United Nations agency for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) stated that the number of people displaced by heavy rains and floods in Somalia has doubled in one week from 334,800 in the preceding week. Over half a million more people have been affected, bringing the total of affected people to 1.7 million, up from 1.17 million a week before. The International Rescue Committee (IRC) issued an alarm in response to severe flooding, warning that in addition to the internal displacement, thousands of homes and shelters have been destroyed and 1.5 million hectares of land could be destroyed in areas where the population rely heavily on agricultural productivity for their livelihoods. Some 5,433 populated areas are located in the flood risk zone of the Jubba and Shebelle rivers.

According to data from Floodlist, the level of the Jubba River rose by more than 5 metres above the long term average for this time of year. Across the Horn of Africa – in Somalia, Ethiopia and Kenya – extensive flooding has been reported since October. The rains are taking place within the ‘short rain’ period from October to December which are associated with the weather patterns of the region, but this season’s floods have been described by the UN as a once in a century event and associated with the El Nino phenomenon. The floods follow on the back of a period of three consecutive years of intense drought which decimated crops and caused abnormally high livestock deaths, as reported in February last year by The Water Diplomat.

Reliefweb reports that a Humanitarian Response Plan for 2023 which sought to raise US$2.6 billion to provide support to 7.6 million people remained underfunded, with only 39% of envisaged costs covered. The organization also makes the link to COP 28, stating that “people on the frontlines of the climate crisis in Somalia have done the least to contribute to climate change but are experiencing the gravest losses - this is the definition of climate injustice. COP28, less than two weeks away, presents the opportunity to address the impacts of climate on conflict-affected, climate-vulnerable communities with solutions that will target resilience, adaptation, and unequal gaps in climate finance.’’

Somalia is ranked in 172nd place out of 182 countries on the ND Gain country index which measures the vulnerability to climate change. The country already records some of the highest average temperatures in the world: in the southwest, the average annual temperature is 29°C. The number of days with a daily maximum temperature above 35° C is projected to rise strongly. The country is vulnerable to flooding and has already experienced major floods in 2006, 2018 and 2019. According to UNHCR there is evidence of increasing frequency and severity of flooding in Somalia.

The Juba and Shabelle river basins are the two most significant river basins in the country, both of which rise in the Ethiopian highlands, which contribute to 90% of the flow of these rivers. The plains of the Juba-Shabelle rivers are very fertile, and generally provide sufficient water for crop production, livestock and for domestic use. The low-lying areas along the Juba and Shabelle rivers often experience flooding,